Menu

-

MenuBack

- Home

-

Categories

-

-

Categories

-

Vegetable Seeds

-

Varieties by Country

- Varieties from Armenia

- Varieties from BiH

- Varieties from Croatia

- Varieties from France

- Varieties from Germany

- Varieties from Greece

- Varieties from Hungary

- Varieties from India

- Varieties from Italy

- Varieties from Japan

- Varieties from North Macedonia

- Varieties from Peru

- Varieties from Russia

- Varieties from Serbia

- Varieties from Slovenia

- Varieties from Spain

- Varieties from Thailand

- Varieties from Turkey

- Varieties from USA

- Tomato Seeds

- Corn Seeds

- Gourd family

- Bean family

- Cucumber Seeds

- Pepper Seeds

- Carrot family

- Onion family

- Lettuce Seeds

- Potato family

- Cabbage family

- Radish Seeds

- Beetroot family

- Watermelon Seeds

- Melon Seeds

- Cauliflower Seeds

- Sunflower family

-

Varieties by Country

- Fruit Seeds

- Chili - Habanero Seeds

- Medicinal Herb Seeds

- Climbing Plants Seeds

- Trees Bonsai Seeds

- Palm Seeds

- Ornamental Grasses Seeds

- Tobacco Seeds

-

Vegetable Seeds

-

-

-

-

- NEW PRODUCTS

- Create account

- Delivery - Payment

- FAQ

- Home

-

- Large Packets of Seeds

- Giant Plants Seeds

- Vegetable Seeds

- Varieties by Country

- Varieties from Armenia

- Varieties from BiH

- Varieties from Croatia

- Varieties from France

- Varieties from Germany

- Varieties from Greece

- Varieties from Hungary

- Varieties from India

- Varieties from Italy

- Varieties from Japan

- Varieties from North Macedonia

- Varieties from Peru

- Varieties from Russia

- Varieties from Serbia

- Varieties from Slovenia

- Varieties from Spain

- Varieties from Thailand

- Varieties from Turkey

- Varieties from USA

- Tomato Seeds

- Corn Seeds

- Gourd family

- Bean family

- Cucumber Seeds

- Pepper Seeds

- Carrot family

- Onion family

- Lettuce Seeds

- Potato family

- Cabbage family

- Radish Seeds

- Beetroot family

- Watermelon Seeds

- Melon Seeds

- Cauliflower Seeds

- Sunflower family

- Varieties by Country

- Fruit Seeds

- Chili - Habanero Seeds

- Medicinal Herb Seeds

- Climbing Plants Seeds

- Trees Bonsai Seeds

- Banana Seeds

- Palm Seeds

- Ornamental Grasses Seeds

- Tobacco Seeds

- Flower Seeds

- Cactus Seeds

- Water plants seeds

- Sowing Instructions

- Fruit and vegetable molds

- Mushroom Mycelium

- Plant Bulbs

- Bamboo seeds

- Ayurveda Plants

- F1 Hybrid Seeds

- Packaging and stuff

- Cold-resistant plants

- Plants Care

- Organic Spices

- Delivery - Payment

- No PayPal and Card payment X

Last Product Reviews

Out of the two seeds, one germinated and the other one was dead and floatin...

By

Riikka H on 07/03/2024

Riikka H on 07/03/2024

Verified Purchase

Best sellers

There are 1317 products.

Showing 1246-1260 of 1317 item(s)

Korean mint Seeds, blue...

Price

€1.85

(SKU: MHS 71)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>KOREAN MINT SEEDS, BLUE LICORICE (AGASTACHE RUGOSA)</strong></h2>

<h2><span><span style="color:#ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 25 Seeds.</strong></span><strong></strong></span></h2>

<p>Agastache rugosa or Purple Giant Hyssop is a seriously erect perennial with stiff, toothed leaves having a wonderful spearmint-licorice smell to leaves & flowers. As a garden ornamental, it is nearly identical to A. foeniculum with which it hybridizes, the cultivar 'Blue Fortune' being a cross of both species.</p>

<p>The bluish purple stubby flower-spikes on Korean Mint's long stems are suitable for bouquets, & long-lasting in the summer garden. Shown above in July (2002) & below respectively in June & July (2004), it is not unusual for flowers to linger until October.</p>

<p>The flowers are usually two to four inches tall (now & then longer), above three foot tall stems from a slowly spreading clump.</p>

<p>In June & early July the flowers are quite stubby, fat & conical. By mid-August if not sooner, the blooms, which keep growing, are reaching their full four inch height & are preparing to seed. When they are turning to seed, they begin to look like furry green shortened tabby-cats' tails.</p>

<p>Extract of A. rugosa are mixed with extracts of Pogostemon patchouli in herbal perfumes associated with the hippy era. THe same two herbs as powders or liquids continue to be offered medicinally as Patchouli or Huo-xiang.</p>

<p>A native of China, Vietnam, Laos, Korea, & Japan, Purple Giant Hyssop has long been used in traditional Chinese herbal remedies. It is one of "the fifty fundamental herbs" & reputedly assists an upset stomach, arrests sweats or fever, summertime colds, & heightens energy.</p>

<p>Whether most of the alleged uses are malarky or not is difficult to assess on the basis of the available studies, most of which were concocted in China by advocates rather than impartial researchers. A study by Wang et al conducted at China's Agricultural University of Hebei,in 2001 found that A .rugosa extracts was one of many effective herbal fungicides for potato crops. It's usefulness as a human medicine is not as clear-cut, as the majority of studies are very poorly modeled. The best resarch has been on methods of improving essential oil production for commercial uses, rather than efficacy.</p>

<p>Antiviral Compounds from Plants by J. B. Hudson (Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 1990) indicates that this hyssop may have a valid antiviral effect which would support it's use as a summer cold remedy, except that it had a measurable effect only when used in alarmingly high doses, the plant's isoflavones having such a low absorption rate from the intestines that claims for it being "potent" are at best a serious exaggeration. But by the tepid evidence thus far available, neither is not entirely devoid of merit.</p>

<p>The leaves & flowers do at the very least make a good herbal tea, one of the best to be gathered fresh from the garden. It seems a reasonable guess that it has the same stomach-settling properties as an ordinary mint tea, but also the same possibility of upsetting the stomach in people who are sensitive to mint.</p>

<p>For dry flowers, hang a long-stemmed bunch flower-heads-down from the ceiling in a warm dry part of the house. In a few days you have perfect dried flowers. Agastache holds its shape & color very well, & will also carry a lingering scent for use in sachets. The late-season larger green "tails" are also worthy of drying.</p>

<p>A forgiving, hardy perennial, it will do well in average to loamy soil, with full or partial sunlight, & is drought-tolerant once established hence a good choice for a roadside sun-garden, which is how we are using it.</p>

<h2>TRADITIONAL USES</h2>

<p>In Korea, it is called (방아잎, bangannip), and used for Korean pancake and stew, more specifically for Bosintang and Chu-eo-tang. Chu-eo-tang is a soup or stew cooked with Chinese muddy loach. It is called (Chinese: 藿香; pinyin: huò xiāng) in Chinese and it is one of the 50 fundamental herbs used in traditional Chinese medicine.</p>

<p>Chemicals isolated from Agastache rugosa have some antibacterial properties.[5] The extracts have shown antifungal activity in in vitro experiments. Agastache rugosa may have anti-atherogenic properties.</p>

MHS 71 (25 S)

Variety from India

White Eggplant Seeds

Price

€1.85

(SKU: VE 116)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>White Eggplant Seeds</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 10 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>White-skinned eggplant that produces early! Produces 25 – 30 cm long, pearly-white fruits with flesh that is delicate and sweet, without bitterness, with a succulent mushroom-like flavor. With white flesh, this eggplant variety can grow anywhere in the World.<br /><br /></p>

<p>White eggplants are slightly curved and oblong, averaging 25-30 centimeters in length. The outer skin is smooth and bright white with one bulbous end that tapers slightly to a green calyx. The cream-colored inner flesh is dense with many, edible white seeds. When cooked, White eggplants are creamy and mild with a light sweet flavor.</p>

<p>White eggplants, botanically classified as Solanum melongena, are a part of the Solanaceae, or nightshade family along with potatoes, tomatoes, and peppers. There are two categorically different White eggplants, an ornamental species, and the commonly domesticated species.</p>

<p>White eggplant has been traditionally used in Asian medicine dating back to 1330. A Chinese treatise known as the Yinshan Zhengyao by Hu Sihui depicts principles of safe food and cites text and images of eggplants. In India, Ayurvedic medicine also uses eggplant to aid in the treatment of disease, and its roots are used to reduce symptoms of asthma.</p>

<p>White eggplants are native to India and Bangladesh and have been cultivated since ancient times. They were then spread to Asia and Europe via trade routes. Today White eggplants can be found in specialty grocers and farmers' markets in Asia, Europe, and the United States.</p>

<p>Heirloom<br />Zones: 3-9<br />Germination: 8-10 days<br />Days to Maturity: 70 days<br />Head Size: 25 – 30 cm<br />Head Color: White<br />Fruit Weight: 350 – 400 g</p>

VE 116 (10 S)

White Sesame Seed (Sesamum...

Price

€1.25

(SKU: VE 65 W (1g))

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>White Sesame Seed (Sesamum indicum)</strong></h2>

<h2 class=""><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 1g (350) seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Sesame (Sesamum indicum) is native to the Old Word tropics and is one of the oldest cultivated plants in the world. Sesame oil is not mentioned in the Bible, but appears to have been important in non-Hebrew cultures 2,000 to 4,000 years ago. It was a highly prized oil crop of Babylon and Assyria at least 4,000 years ago. Today, India and China are the world's largest producers of sesame, followed by Burma, Sudan, Mexico, Nigeria, Venezuela, Turkey, Uganda and Ethiopia. World production in 1985 was 2.53 million tons on 16.3 million acres. Sesame seeds are approximately 50% oil and 25% protein. They are used in baking, candy making, and other food industries. The oil contains about 47% oleic and 39% linoleic acid. Sesame oil and foods fried in sesame oil have a long shelf life because the oil contains an antioxidant called sesamol. Sesame oil is also used in the manufacture of soaps, paints, perfumes, pharmaceuticals and insecticides.</p>

<p> </p>

<p>The expression "open sesame" made famous in the story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, one of the tales from the Arabian Nights, is probably based on the sesame seed capsule. Some authorities have suggested that this expression was adopted by the author of the stories because the capsules burst open at maturity with the slightest touch. Other interpretations suggest that it comes from the popping sound of the mature pod as it opens, like the sudden pop of a lock springing open. Because of the shattering characteristic, sesame has been grown primarily on small plots that are harvested by hand. The discovery of an indehiscent (nonshattering) mutant by Langham in 1943 resulted in the development of a high yielding, shatter-resistant variety that retained its seeds during harvesting. Langham also discovered that indehiscent trait in sesame was controlled by one pair of recessive alleles. Apparently the title of "Sesame Street" is derived from the phrase "open sesame," presumably to inject curiosity and excitement into the title of this popular TV program for children.</p>

<p> </p>

<p>According to Oplinger et al. (1990), the flowers of sesame are typically self pollinated, although they may be cross pollinated by insects. No insect pollinators were observed on the plants grown at Wayne's Word. The growth of sesame is indeterminant: the plant continues to produce leaves, flowers and seed capsules throughout the warm summer months and into the fall.</p>

<p> </p>

<p>The flowers of sesame (Sesamum indicum) are similar in shape to devil's claw plants (Martynia and Proboscidea). In fact, sesame belongs to the same family Pedaliaceae, although some botanists have retained devil's claws in the Martyniaceae. Sesame seeds are an important seed crop. They are sprinkled on breads, cakes, cookies and candies and are the source of a valuable oil.</p>

<p> </p>

<p>Sesame seeds from the herb (Sesamum indicum) are an important world seed crop. The tasty seeds are sprinkled on breads, cakes, cookies and candies and they are the source of a valuable oil. The cake remaining after pressing or extraction makes an excellent livestock food, and in times of famine is eaten by people. The seeds are eaten toasted, or crushed and sweetened to make the Middle Eastern candy known as halva. Middle Eastern tahini is sesame paste made from hulled, lightly roasted seeds. The black seeds (left) are unhulled. Hulled seeds (right) are white.</p>

<p> </p>

<p>Flower of the North American Proboscidea louisianica ssp. louisianica. The yellow lines in the corolla throat are nectar guide lines that direct pollinator bees to the nectar source. This species was formerly placed in the Martyniaceae along with Martynia and Ibicella. It is now placed in the Pedaliaceae, along with sesame (Sesamum indicum), Uncarina and Harpagophytum.</p><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

VE 65 W (1g)

Lilac Seeds (Syringa vulgaris)

Price

€1.55

(SKU: T 59)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><span style="font-size:14pt;"><strong>Lilac Seeds (Syringa vulgaris)</strong></span></h2>

<h2><span style="color:#ff0000;font-size:14pt;"><strong>Price for Package of 10 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Syringa vulgaris originates from Europe. Great bonsai tree potential. If left to grow naturally, it reaches 8 to 10 feet tall. A small tree that with age develops deeply furrowed bark. This species of Lilac produces suckers new shoots that sprout from the base of the shrub, or from the roots. Is very tolerant of hard pruning necessary for bonsai cultivation. Green heart-shaped leaves are smooth and appear before the flowers bloom. At Fall, the leaves turn yellow-green. The light purple flowers grow in large clusters, from May to June and have one of the most powerful fragrances emitted by a plant. Hardiness zones 3-7, (-15ºC/5ºF, -37ºC/-35ºF) in Winter. Adptable to a wide range of soils. Lilacs prefer well-drained, slightly alkaline soil and plenty of sunshine for optimum growth and blooming. Although Lilacs love water, they don't enjoy soggy soil. Without proper drainage, Lilacs will do little growing and produce fewer blossoms.</p>

<p><strong>Germination</strong></p>

<p>For faster germination, soak the seeds in slightly hot water for 24-48 hours, followed by one month of cold stratification before sowing at 1/4" deep in sterile gardening soil. Keep damp soil, not soaking wet. Keep pot in warm situation 68-75ºF. Germination usually occurs in 2-4 weeks. It can be a lot more depending on their degree of unbroken dormancy, don't give up.</p>

<p><strong>Scarification / Stratification </strong></p>

<p>This will break their dormancy. It creates a cold and moist environment for the seeds. Mixed in seeds with slightly moistened vermiculite or peat, only damp in a ziplock bag. Close zip bag shut and store it in the salad crisper compartment of your refrigerator. If any seeds begin to sprout during the cold stratification, simply remove the seed and plant.</p>

<p><strong>WIKIPEDIA:</strong></p>

<p>Syringa vulgaris (lilac or common lilac) is a species of flowering plant in the olive family Oleaceae, native to the Balkan Peninsula, where it grows on rocky hills. This species is widely cultivated as an ornamental and has been naturalized in other parts of Europe (UK, France, Germany, Italy, etc.), as well as much of North America. It is not regarded as an aggressive species, found in the wild in widely scattered sites, usually in the vicinity of past or present human habitations.</p>

<p>S. vulgaris is a large deciduous shrub or multistemmed small tree, growing to 6–7 m (20–23 ft) high, producing secondary shoots ("suckers") from the base or roots, with stem diameters up to 20 cm (8 in), which in the course of decades may produce a small clonal thicket.[7] The bark is grey to grey-brown, smooth on young stems, longitudinally furrowed, and flaking on older stems. The leaves are simple, 4–12 cm (2–5 in) and 3–8 cm broad, light green to glaucous, oval to cordate, with pinnate leaf venation, a mucronate apex, and an entire margin. They are arranged in opposite pairs or occasionally in whorls of three. The flowers have a tubular base to the corolla 6–10 mm long with an open four-lobed apex 5–8 mm across, usually lilac to mauve, occasionally white. They are arranged in dense, terminal panicles 8–18 cm (3–7 in) long. The fruit is a dry, smooth, brown capsule, 1–2 cm long, splitting in two to release the two-winged seeds.</p>

<p><strong>Garden history</strong></p>

<p>Lilacs — both S. vulgaris and S. × persica the finer, smaller "Persian lilac", now considered a natural hybrid — were introduced into European gardens at the end of the 16th century, from Ottoman gardens, not through botanists exploring the Balkan habitats of S. vulgaris.[12] The Holy Roman Emperor's ambassador, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, is generally credited with supplying lilac slips to Carolus Clusius, about 1562. Well-connected botanists, such as the great herbalist John Gerard, soon had the rarity in their gardens: Gerard noted that he had lilacs growing “in very great plenty” in 1597, but lilacs were not mentioned by Shakespeare,[13] and John Loudon was of the opinion that the Persian lilac had been introduced into English gardens by John Tradescant the elder.[14] Tradescant's Continental source for information on the lilac, and perhaps ultimately for the plants, was Pietro Andrea Mattioli, as one can tell from a unique copy of Tradescant's plant list in his Lambeth garden, an adjunct of his Musaeum Tradescantianum; it was printed, though probably not published, in 1634: it lists Lilac Matthioli. That Tradescant's "lilac of Mattioli's" was a white one is shown by Elias Ashmole's manuscript list, Trees found in Mrs Tredescants Ground when it came into my possession (1662):[15] "Syringa alba".</p>

<p>In the American colonies, lilacs were introduced in the 18th century. Peter Collinson, F.R.S., wrote to the Pennsylvania gardener and botanist John Bartram, proposing to send him some, and remarked that John Custis of Virginia had a fine "collection", which Ann Leighton interpreted as signifying common and Persian lilacs, in both purple and white, "the entire range of lilacs possible" at the time.</p>

<p><strong>Cultivation</strong></p>

<p>The lilac is a very popular ornamental plant in gardens and parks, because of its attractive, sweet-smelling flowers, which appear in early summer just before many of the roses and other summer flowers come into bloom.</p>

<p>In late summer, lilacs can be attacked by powdery mildew, specifically Erysiphe syringae, one of the Erysiphaceae.[18] No fall color is seen and the seed clusters have no aesthetic appeal.</p>

<p>Common lilac tends to flower profusely in alternate years, a habit that can be improved by deadheading the flower clusters after the color has faded and before seeds, few of which are fertile, form. At the same time, twiggy growth on shoots that have flowered more than once or twice can be cut to a strong, outward-growing side shoot.</p>

<p>It is widely naturalised in western and northern Europe.[8] In a sign of its complete naturalization in North America, it has been selected as the state flower of the state of New Hampshire, because it "is symbolic of that hardy character of the men and women of the Granite State".[19] Additional hardiness, for Canadian gardens, was bred for in a series of S. vulgaris hybrids by Isabella Preston, who introduced many of the later-blooming varieties, whose later-developing flower buds are better protected from late spring frosts; the Syringa x prestoniae hybrids range primarily in the pink and lavender shades</p>

T 59

Variety from Italy

Borlotto Lingua Di Fuoco...

Price

€1.95

(SKU: VE 146 (5.5g))

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

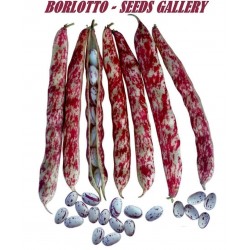

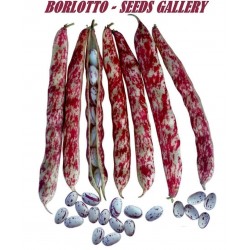

<h2 class=""><strong>Borlotto Lingua Di Fuoco Nano Bean Seeds (dwarf)</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 10 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Borlotto Lingua di Fuoco (traditional Italian variety) sounds more like an opera with aphrodisiac qualities rather than one of the eldest varieties of Borlotto bean.</p>

<p>Lingua di Fuoco literally translates as ‘Tongue of Fire’.</p>

<p>Borlotto Lingua Di Fuoco' is a mid-early Bean, with a long, inflated pod containing seven cream coloured beans. The height of the plant is 45-50 centimetres and the pods themselves have a length of 14-15 cm. The grains are large and easily removed from the pods.</p>

<p>Loved for their excellent flavour, colour and versatility, Borlotto is the most commonly used heritage bean in Italy for cooking, they are basically the Italian version of kidney beans. This dual-purpose variety can be eaten young in the pod either raw or cooked or can be shelled and used as a bean.</p>

<p>The pods look wonderful in the garden and are stunning chopped into salads. Its gorgeous colour is almost whimsical as you break open the pods to retrieve the plump beans inside. With a creamy taste and a soft nutty consistency, it is quite the most beautiful bean in the world.</p>

<p><strong>Where to grow:</strong></p>

<p>Borlotto beans are grown just like runner beans. They prefer to grow in moist, fertile soil in a sunny, sheltered spot away from strong winds. Prepare the soil for planting by digging over and adding plenty of organic material, this will help to improve the soil's moisture-retaining ability and fertility.</p>

<p>Beans can also be grown in pots. Choose pots at least 45cm (18in) in diameter and make sure there are plenty of drainage holes. Fill with a mixture of equal parts loam-based compost and loam-free compost.</p>

<p><strong>Supporting plants:</strong></p>

<p>If you wish to train the plant vertically, create support before planting. Either make a wigwam with canes, lashed together with string at the top, or create a parallel row of canes, which have their tops tightly secured to a horizontal cane. Add to the ornamental appeal of wigwams by planting a few fragrant sweetpeas alongside them. These will twine together as they climb, attracting pollinating insects to the beans, and providing flowers to pick at the same time as the crop</p>

<p>Sowing: Sow indoors late April and May, outdoors in late May to June.</p>

<p>Even when temperatures are not below freezing, cold air can damage bean plants, so don't plant too early. Plant outdoors only after the last frosts, May onwards. Sowing seeds early indoors gives a faster and more reliable germination rate. Beans sown directly outside often germinate poorly or get attacked by slugs.</p>

<p>Avoid problems by sowing seeds in late April and May in pots or root trainers in the greenhouse. Robust young plants will be ready to plant outside within about 5 weeks, growing away far quicker than outdoor sowings.</p>

<p>Sow a single bean seed, 4cm (1.5in) deep, in root trainers or into a 7.5cm (3in) pot filled with multipurpose compost. Water well, label and place on a sunny windowsill to germinate. Seedlings will be ready to plant out after about three weeks. Before planting, put in a cold frame to acclimatise.</p>

<p>Alternatively, beans can be sown directly in the soil between the second half of May and the middle of June. Plant two seeds next to your support about 5cm (2in) deep. Water well. After germination remove the smaller and less robust of the two young plants. As they grow, ensure the plants continue to twine around their canes.</p>

<p><strong>Cultivation:</strong></p>

<p>Having shallow roots regular and plentiful watering is vital. Whilst they will prove drought tolerant, beans should be watered particularly heavily, twice a week in dry weather, both when the flower buds appear and once they're open, ensure maximum pod development. Mulch when conditions are dry.</p>

<p>Don’t hoe around bean plants too deeply or you may damage the roots.</p>

<p>Beans capture nitrogen from the air, so make sure the soil contains the other essential ingredients, phosphorus and potassium. So for the fertiliser use something like 10-20-10. They leave the soil nitrogen-enriched even after harvest</p>

<p><strong>Harvesting: 55 days</strong></p>

<p>Ready for harvesting as green pods after 55 days, or shelling semi-dry after 70 to 80 days. The more you pick, the more they produce. Most should bear pods from late July and cropping of all types can continue until the first frosts, or longer if plants are protected.</p>

<p>Leave the pods on the plant until the shells have changed colour from green to a fully white and red colour. Check that beans inside have turned from green to similar colour to shells. Harvest and shell the beans</p>

<p><strong>Storing:</strong></p>

<p>The beans will store best if you remove the pods, spread them on trays and place them in a warm dry room for a few days to dry out completely before storing them in clean jars in a cool dry place. Discard any that are discoloured or damaged. The beans will then keep for a few years. Check them over periodically to make sure no insects have got in as you would with any store cupboard food.</p>

<p>To cook the dried beans, they will need soaking first, they are best left overnight in a big bowl of water. While the soaking is not strictly necessary, it shortens cooking time and results in more evenly textured beans. In addition, discarding one or more batches of soaking water leaches out hard-to-digest complex sugars that can cause flatulence.</p>

<p>Before using in a recipe, boil the soaked beans for at least 45 minutes, or boil for ten minutes, tip off the water and add fresh water, then bring to the boil again and boil for at least another 30 to 45 minutes. Don’t add salt to these first boilings as it can make the beans rather hard.</p>

<p><strong>Origin:</strong></p>

<p>Phaseolus vulgaris, the common bean, is a herbaceous annual plant domesticated in the ancient Andes and now grown worldwide for its edible bean, popular both dry and as a green bean. The leaf is occasionally used as a leaf vegetable, and the straw is used for fodder.</p>

<p>The common bean is a highly variable species with a long history. Bush varieties form erect bushes 20 to 60cm (8 to 24in) tall, while pole or running varieties form vines 180 to 270cm (6 to 9ft) tall.</p>

<p><strong>Nomenclature:</strong></p>

<p>Borlotto beans are known as Saluggia Beans or Salugia in Piedmontese.</p>

<p>Saluggia is a comune (municipality) in the Province of Vercelli in the Italian region Piedmont, located about 30 km northeast of Turin, it is renowned in Italy and abroad for the production of beans.</p>

<p>In poorer areas of Italy where meat dishes were few and far between, beans were known as 'carne dei poveri’ meaning ‘the meat of the poor’. Funny how times change!</p>

<p>Occasionally they are referred to as cranberry beans, from their mottled cranberry-red and ivory markings.</p>

<p><strong>Translation:</strong></p>

<p>In Italian, Borlotto is the singular form, while Borlotti is plural</p>

<p>Fagiolo means bean, while Fagioli means beans.</p>

<p>Nano means 'dwarf' and is the singular form, while Nani is plural</p><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

VE 146 (5.5g)

Cowpea Seeds (Vigna...

Price

€1.25

(SKU: P 277)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

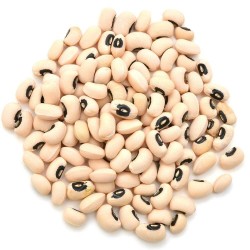

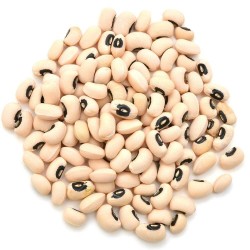

<h2><strong>Cowpea Seeds (Vigna unguiculata)</strong></h2>

<h2 class=""><strong><span style="color: #ff0000;">Price for Package of 20 (5g) seeds.</span></strong></h2>

<p>The cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) is one of several species of the widely cultivated genus Vigna. Four subspecies are recognised, of which three are cultivated (more exist, including V. textilis, V. pubescens, and V. sinensis)</p>

<p>Cowpeas are one of the most important food legume crops in the semiarid tropics covering Asia, Africa, southern Europe, and Central and South America. A drought-tolerant and warm-weather crop, cowpeas are well-adapted to the drier regions of the tropics, where other food legumes do not perform well. It also has the useful ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen through its root nodules, and it grows well in poor soils with more than 85% sand and with less than 0.2% organic matter and low levels of phosphorus.</p>

<p> In addition, it is shade tolerant, so is compatible as an intercrop with maize, millet, sorghum, sugarcane, and cotton. This makes cowpeas an important component of traditional intercropping systems, especially in the complex and elegant subsistence farming systems of the dry savannas in sub-Saharan Africa. In these systems the haulm (dried stalks) of cowpea is a valuable by-product, used as animal feed.</p>

<p>Research in Ghana found that selecting early generations of cowpea crops to increase yield is not an effective strategy. Francis Padi from the Savannah Agricultural Research Institute in Tamale, Ghana, writing in Crop Science, suggests other methods such as bulk breeding are more efficient in developing high-yield varieties.</p>

<p>According to the USDA food database, the leaves of the cowpea plant have the highest percentage of calories from protein among vegetarian foods.</p>

<p><strong>Taxonomy and etymology</strong></p>

<p>Vigna unguiculata is a member of the Vigna (peas or beans) genus. Unguiculata is Latin for "with a small claw", which reflects the small stalks on the flower petals. All cultivated cowpeas are found within the universally accepted V. unguiculata subspecies unguiculata classification, which is then commonly divided into four cultivar groups: Unguiculata, Biflora, Sesquipedalis, and Textilis.</p>

<p> Some well-known common names for cultivated cowpeas include Lesera/ Dangbodi (লেছেৰা/ ডাংবডি) in Assamese, black-eye pea, southern pea, yardlong bean, catjang and Crowder Pea.[8] The classification of the wild relatives within V. unguiculata is more complicated, with over 20 different names having been used and between 3 and 10 subgroups described. The original subgroups of stenophylla, dekindtiana and tenuis appear to be common in all taxonomic treatments, with the earlier described variations pubescens and protractor being raised to sub species level by a 1993 charactisation.</p>

<p>The first written reference using cowpea appeared in 1798 in the United States. The name was most likely acquired due to their use as a fodder crop for cows. The common name of black-eyed pea, used for the unguiculata cultivar group, describes the presence of a distinctive black spot at the hilum of the seed. Black-eyed peas were first introduced to the southern states in the United States and some early varieties had peas squashed closely together in their pods, leading to the other common names of southern pea and crowder-pea. Sesquipedalis in Latin means "foot and a half long", and this subspecies which arrived in the United States via Asia is characterised by unusually long pods, leading to the common names of yardlong bean, asparagus bean and Chinese long-bean.</p>

<p> In West Africa the plant is named niebe, wake or ewa.</p>

<p><strong>Description</strong></p>

<p>There is a large morphological diversity found within the crop, and the growth conditions and grower preferences for each variety vary from region to region.</p>

<p><strong>History</strong></p>

<p>Although there is no archaeological evidence for early cowpea cultivation the centre of diversity of the cultivated cowpea is West Africa, leading to the current consensus that this is the likely centre of origin and place of early domestication. In 2300 BC the cowpea is believed to have made its way into South East Asia where secondary domestication events may have occurred. The first written references to the cowpea were in 300BC and they probably reached Central and North America during the slave trade through the 17thto early 19th centuries.</p>

<p><strong>Cultivation</strong></p>

<p>Cowpeas are grown mostly for their edible beans, although the leaves, green peas and green pea pods can also be consumed, meaning the cowpea can be used as a food source before the dried peas are harvested. Cowpeas thrive in poor dry conditions, growing well in soils up to 85% sand.[18] This makes them a particularly important crop in arid, semi-desert regions where not many other crops will grow. As well as an important source of food for humans in poor arid regions the crop can also be used as feed for livestock. This predominately occurs in India, where the stock is fed cowpea as forage or fodder.[10] The nitrogen fixing ability means that as well as functioning as a sole-crop, the cowpea can be effectively intercropped with sorghum, millet, maize, cassava or cotton.</p>

<p><strong>Pests and diseases</strong></p>

<p>Insects are a major factor in the low yields of African cowpea crops, and they affect each tissue component and developmental stage of the plant. In bad infestations insect pressure is responsible for over 90% loss in yield. The legume pod borer Maruca (testulalis) vitrata, is the main pre-harvest pest of the cowpea. It causes damage to the flower buds, flowers and pods of the plant. Other important pests include pod sucking bugs, thrips and the post-harvest weevil Callosobruchus maculatus.</p>

<p><strong>Culinary use</strong></p>

<p>In Tamil Nadu, India, between the Tamil months of Maasi (February) and Panguni (March), a cake-like dish called kozhukattai (steamed sweet dumplings – also called Sukhiyan in Kerala) is prepared with cooked and mashed cowpeas mixed with jaggery, ghee, and other ingredients. Thatta payir in sambar and pulikkuzhambu (spicy semisolid gravy in tamarind paste) is a popular dish in Tamil Nadu.</p>

<p>In Sri Lanka, cowpeas (කවුපි in Sinhala) are cooked in many different ways, one of which is with coconut milk.</p>

<p>In Turkey, cowpeas can be lightly boiled, covered with olive oil, salt, thyme, and garlic sauce, and eaten as an appetizer; they are cooked with garlic and tomatoes; and they can be eaten in bean salad.</p>

<p><strong>Nutrition and health</strong></p>

<p>Cowpeas provide a rich source of proteins and calories, as well as minerals and vitamins. A cowpea seed can consist of 25% protein and is low in anti-nutritional factors. This diet complements the mainly cereal diet in countries that grow cowpeas as a major food crop.</p>

<p><strong>Production and consumption</strong></p>

<p>Most cowpeas are grown on the African continent, particularly in Nigeria and Niger which account for 66% of world cowpea production. The Sahel region also contains other major producers such as Burkina Faso, Ghana, Senegal and Mali. Niger is the main exporter of cowpeas and Nigeria the main importer. Exact figures for cowpea production are hard to come up with as it is not a major export crop. A 1997 estimate suggests that cowpeas are cultivated on 12.5 million hectares and have a worldwide production of 3 million tonnes.[10] While they play a key role in subsistence farming and livestock fodder, the cowpea is also seen as a major cash crop by Central and West African farmers, with an estimated 200 million people consuming cowpea on a daily basis.</p>

<p>According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), as of 2012, the average cowpea yield in Western Africa was an estimated 483 kg/ha,[26] which is still 50% below the estimated potential production yield. In some tradition cropping methods the yield can be as low as 100 kg/ha.</p>

<p>Outside Africa, the major production areas are Asia, Central America, and South America. Brazil is the world's second-leading producer of cowpea seed, producing 600,000 tonnes annually.[29] The amount of protein content of cowpea's leafy parts consumed annually in Africa and Asia is equivalent to 5 million tonnes of dry cowpea seeds, representing as much as 30% of the total food legume production in the lowland tropics.</p><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

P 277 (2.7 g)

Coming Soon

Okra Burgundy Seeds...

Price

€1.85

(SKU: VE 8 R)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8" />

</head>

<body>

<h2><strong>Okra Burgundy Seeds Clemson Spineless</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 15 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<div>This variety is one of the most popular, prolific and reliable strains available. Straight, 6-7 inch, red pods are slightly ridged and definitely spineless. Plants 3 ft. high, produce an abundance of dark green, 6-inch slightly tapered and ribbed, straight, pointed pods without spines. Best when 2 1/2-3 in. long. Fine quality and prolific. First harvest around 60 days after seed is sown. </div>

<div>Days to Germination: 10-14</div>

<div>Days To Harvest: 55-65</div>

<div>Planting Depth: 1/2 - 3/4 in.</div>

<div>Spacing, Row: 3 foot</div>

<div>Plant Height: 3 ft.</div>

<div>Light: Full Sun</div>

<h3><strong>Sowing instructions:</strong></h3>

<div>Sow under cover 4-6 weeks before last frost or directly outside in warmer areas from late spring.</div>

<div>Sow 1/2-3/4 inch deep, 2 to a pot and thin to strongest seedling, or thinly in rows, thinning to 18-24 inches between plants.</div>

<div>Plant out after last frost.</div>

<div>Sunny location required in order to maximise harvest.</div>

<div>Harvest pods when they are young and tender, 2 1/2 - 3 inches long. </div>

<div>Keep ripe pods picked to encourage production.</div>

<div>showing.</div>

<div>Harvest the beans when the pods are well fat and the seed still soft.</div>

</body>

</html>

VE 8 R (15 S)

Variety from Italy

Lettuce Seeds BATAVIA...

Price

€1.85

(SKU: PL 5)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>Lettuce Seeds BATAVIA BIONDA DI PARIGI</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;" class=""><strong>Price for Package of 1000 (1g) seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Italian Heirloom Batavia Bionda Di Parigi is a medium-early variety that produces a large, and heavy head, which is crisp and golden. A large tightly wrapped round head with light green tender leaves and pronounced crunchy ribs.</p>

<h3><strong>When to Plant</strong></h3>

<p>In spring, sow lettuce in cold frames or tunnels six weeks before your last frost date. Start more seeds indoors under lights at about the same time, and set them out when they are three weeks old. Direct seed more lettuce two weeks before your average last spring frost date. Lettuce seeds typically sprout in two to eight days when soil temperatures range between 55 and 75 degrees.</p>

<p>In fall, sow all types of lettuce at two-week intervals starting eight weeks before your first fall frost. One month before your first frost, sow only cold-tolerant butterheads and romaines.</p>

<h3><strong>How to Plant</strong></h3>

<p>Prepare your planting bed by loosening the soil to at least 10 inches deep. Mix in an inch or so of good compost or well-rotted manure. Sow lettuce seeds a quarter of an inch deep and 1 inch apart in rows or squares, or simply broadcast them over the bed.</p>

<p>Indoors, sow lettuce seeds in flats or small containers kept under fluorescent lights. Harden off three-week-old seedlings for at least two or three days before transplanting. Use shade covers, such as pails or flowerpots, to protect transplants from sun and wind during their first few days in the garden.</p>

<h3><strong>Harvesting and Storage</strong></h3>

<p>Harvest lettuce in the morning, after the plants, have had all night to plump up with water. Wilted lettuce picked on a hot day seldom revives, even when rushed to the refrigerator. Pull (and eat) young plants until you get the spacing you want. Gather individual leaves or use scissors to harvest handfuls of baby lettuce. Rinse lettuce thoroughly with cool water, shake or spin off excess moisture, and store it in plastic bags in the refrigerator. Lettuce often needs a second cleaning as it is prepared for the table.</p><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

PL 5 (1g)

Corn Salad Seeds D'OLANDA A...

Price

€1.55

(SKU: PL 9)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>Corn Salad Seeds D'OLANDA A SEME GROSSO</strong></h2>

<h2 class=""><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 350 (1g) seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Lamb’s lettuce in the UK, valeriana in Italy, corn salad in the USA and mache in France. Larger leaves than Cambrai, soft and tender texture with same great taste and cold resistance A favourite of those from cold climates where it was the first green salad vegetable to emerge from the melting snow. A delightful salad green that will only do well if grown when cold, but has great cold resistance. Direct seed in rows early spring and autumn and thin to 10cm.</p><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

PL 9 (1g)

Giant plant (with giant fruits)

Endive Giant Seeds

Price

€1.65

(SKU: VE 187)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><span><em><strong><span style="text-decoration:underline;color:#000000;">ENDIVE GIANT SEEDS</span><br /></strong></em></span></h2>

<h3><span style="color:#ff0000;"><strong>Package of 100 seeds.</strong></span></h3>

<div>Beware! Once you acquire a taste for this interesting and attractive-looking salad plant, you will find salads based on the ubiquitous Lettuce insipid and dull. Although grown like Lettuce, it has the advantage that it will withstand without complaint both heat and a few degrees of frost. Best if blanched a few days before harvesting and - a personal opinion - tastes better with a home-made French dressing rather than salad cream out of a bottle. If you´ve never grown Endives, do give them a trial.</div>

VE 187 (100 S)

LETTUCE BRASILIANA Seeds

Price

€1.85

(SKU: PL 6)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>LETTUCE BRASILIANA Seeds</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 100 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Brasiliana: Similar in nature to an Iceberg lettuce. Large, tightly wrapped head with crunchy leaves.</p>

<p>Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) is an annual plant of the daisy family Asteraceae. It is most often grown as a leaf vegetable, but sometimes for its stem and seeds. Lettuce was first cultivated by the ancient Egyptians who turned it from a weed, whose seeds were used to produce oil, into a food plant grown for its succulent leaves, in addition to its oil-rich seeds. Lettuce spread to the Greeks and Romans, the latter of whom gave it the name lactuca, from which the English lettuce is ultimately derived. By 50 AD, multiple types were described, and lettuce appeared often in medieval writings, including several herbals. The 16th through 18th centuries saw the development of many varieties in Europe, and by the mid-18th century cultivars were described that can still be found in gardens. Europe and North America originally dominated the market for lettuce, but by the late 20th century the consumption of lettuce had spread throughout the world.</p>

<p>Generally grown as a hardy annual, lettuce is easily cultivated, although it requires relatively low temperatures to prevent it from flowering quickly. It can be plagued with numerous nutrient deficiencies, as well as insect and mammal pests and fungal and bacterial diseases. L. sativa crosses easily within the species and with some other species within the Lactuca genus; although this trait can be a problem to home gardeners who attempt to save seeds, biologists have used it to broaden the gene pool of cultivated lettuce varieties. World production of lettuce and chicory for calendar year 2010 stood at 23 620 000/23,620,000 tonnes, half of which came from China.</p>

<p>Lettuce is most often used for salads, although it is also seen in other kinds of food, such as soups, sandwiches and wraps; it can also be grilled.[3] One variety, the woju (莴苣), or asparagus lettuce, is grown for its stems, which are eaten either raw or cooked. Lettuce is a rich source of vitamin K and vitamin A, and is a moderate source of folate and iron. Contaminated lettuce is often a source of bacterial, viral and parasitic outbreaks in humans, including E. coli and Salmonella. In addition to its main use as a leafy green, it has also gathered religious and medicinal significance over centuries of human consumption.</p>

<p><strong>Taxonomy and etymology</strong></p>

<p>Lactuca sativa is a member of the Lactuca (lettuce) genus and the Asteraceae (sunflower or aster) family.[4] The species was first described in 1753 by Carl Linnaeus in the second volume of his Species Plantarum.[5] Synonyms for L. sativa include Lactuca scariola var. sativa,[1] L. scariola var. integrata and L. scariola var. integrifolia.[6] L. scariola is itself a synonym for L. serriola, the common wild or prickly lettuce.[2] L. sativa also has many identified taxonomic groups, subspecies and varieties, which delineate the various cultivar groups of domesticated lettuce.[7] Lettuce is closely related to several Lactuca species from southwest Asia; the closest relationship is to L. serriola, an aggressive weed common in temperate and subtropical zones in much of the world.</p>

<p>The Romans referred to lettuce as lactuca (lac meaning milk in Latin), an allusion to the white substance, now called latex, exuded by cut stems.[9] This word has become the genus name, while sativa (meaning "sown" or "cultivated") was added to create the species name.[10] The current word lettuce, originally from Middle English, came from the Old French letues or laitues, which derived from the Roman name.[11] The name romaine came from that type's use in the Roman papal gardens, while cos, another term for romaine lettuce, came from the earliest European seeds of the type from the Greek island of Cos, a center of lettuce farming in the Byzantine period.</p>

<p><strong>Description</strong></p>

<p>Lettuce's native range spreads from the Mediterranean to Siberia, although it has been transported to almost all areas of the world. Plants generally have a height and spread of 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm). The leaves are colorful, mainly in the green and red color spectrums, with some variegated varieties. There are also a few varieties with yellow, gold or blue-teal leaves. Lettuces have a wide range of shapes and textures, from the dense heads of the iceberg type to the notched, scalloped, frilly or ruffly leaves of leaf varieties.[14] Lettuce plants have a root system that includes a main taproot and smaller secondary roots. Some varieties, especially those found in the United States and Western Europe, have long, narrow taproots and a small set of secondary roots. Longer taproots and more extensive secondary systems are found in varieties from Asia.</p>

<p>Depending on the variety and time of year, lettuce generally lives 65–130 days from planting to harvesting. Because lettuce that flowers (through the process known as "bolting") becomes bitter and unsaleable, plants grown for consumption are rarely allowed to grow to maturity. Lettuce flowers more quickly in hot temperatures, while freezing temperatures cause slower growth and sometimes damage to outer leaves.[16] Once plants move past the edible stage, they develop flower stalks up to 3 feet (0.9 m) high with small yellow blossoms.[17] Like other members of the tribe Cichorieae, lettuce inflorescences (also known as flower heads or capitula) are composed of multiple florets, each with a modified calyx called a pappus (which becomes the feathery "parachute" of the fruit), a corolla of five petals fused into a ligule or strap, and the reproductive parts. These include fused anthers that form a tube which surrounds a style and bipartite stigma. As the anthers shed pollen, the style elongates to allow the stigmas, now coated with pollen, to emerge from the tube.[15][18] The ovaries form compressed, obovate (teardrop-shaped) dry fruits that do not open at maturity, measuring 3 to 4 mm long. The fruits have 5–7 ribs on each side and are tipped by two rows of small white hairs. The pappus remains at the top of each fruit as a dispersal structure. Each fruit contains one seed, which can be white, yellow, gray or brown depending on the variety of lettuce.</p>

<p>The domestication of lettuce over the centuries has resulted in several changes through selective breeding: delayed bolting, larger seeds, larger leaves and heads, better taste and texture, a lower latex content, and different leaf shapes and colors. Work in these areas continues through the present day.[19] Scientific research into the genetic modification of lettuce is ongoing, with over 85 field trials taking place between 1992 and 2005 in the European Union and United States to test modifications allowing greater herbicide tolerance, greater resistance to insects and fungi and slower bolting patterns. However, genetically modified lettuce is not currently used in commercial agriculture.</p>

<p><strong>History</strong></p>

<p>Lettuce was first cultivated in ancient Egypt for the production of oil from its seeds. This plant was probably selectively bred by the Egyptians into a plant grown for its edible leaves,[21] with evidence of its cultivation appearing as early as 2680 BC.[9] Lettuce was considered a sacred plant of the reproduction god Min, and it was carried during his festivals and placed near his images. The plant was thought to help the god "perform the sexual act untiringly."[22] Its use in religious ceremonies resulted in the creation of many images in tombs and wall paintings. The cultivated variety appears to have been about 30 inches (76 cm) tall and resembled a large version of the modern romaine lettuce. These upright lettuces were developed by the Egyptians and passed to the Greeks, who in turn shared them with the Romans. Circa 50 AD, Roman agriculturalist Columella described several lettuce varieties – some of which may have been ancestors of today's lettuces.</p>

<p>Lettuce appears in many medieval writings, especially as a medicinal herb. Hildegard of Bingen mentioned it in her writings on medicinal herbs between 1098 and 1179, and many early herbals also describe its uses. In 1586, Joachim Camerarius provided descriptions of the three basic modern lettuces – head lettuce, loose-leaf lettuce, and romaine (or cos) lettuce.[12] Lettuce was first brought to the Americas from Europe by Christopher Columbus in the late 15th century.[23][24] Between the late 16th century and the early 18th century, many varieties were developed in Europe, particularly Holland. Books published in the mid-18th and early 19th centuries describe several varieties found in gardens today.</p>

<p>Due to its short lifespan after harvest, lettuce was originally sold relatively close to where it was grown. The early 20th century saw the development of new packing, storage and shipping technologies that improved the lifespan and transportability of lettuce and resulted in a significant increase in availability.[26] During the 1950s, lettuce production was revolutionized with the development of vacuum cooling, which allowed field cooling and packing of lettuce, replacing the previously used method of ice-cooling in packing houses outside the fields.</p>

<p>Lettuce is very easy to grow, and as such has been a significant source of sales for many seed companies. Tracing the history of many varieties is complicated by the practice of many companies, particularly in the US, of changing a variety's name from year to year. This was done for several reasons, the most prominent being to boost sales by promoting a "new" variety or to prevent customers from knowing that the variety had been developed by a competing seed company. Documentation from the late 19th century shows between 65 and 140 distinct varieties of lettuce, depending on the amount of variation allowed between types – a distinct difference from the 1,100 named lettuce varieties on the market at the time. Names also often changed significantly from country to country.[28] Although most lettuce grown today is used as a vegetable, a minor amount is used in the production of tobacco-free cigarettes; however, domestic lettuce's wild relatives produce a leaf that visually more closely resembles tobacco.</p>

<p><strong>Cultivation</strong></p>

<p>A hardy annual, some varieties of lettuce can be overwintered even in relatively cold climates under a layer of straw, and older, heirloom varieties are often grown in cold frames.[25] Lettuces meant for the cutting of individual leaves are generally planted straight into the garden in thick rows. Heading varieties of lettuces are commonly started in flats, then transplanted to individual spots, usually 8 to 14 inches (20 to 36 cm) apart, in the garden after developing several leaves. Lettuce spaced further apart receives more sunlight, which improves color and nutrient quantities in the leaves. Pale to white lettuce, such as the centers in some iceberg lettuce, contain few nutrients.</p>

<p>Lettuce grows best in full sun in loose, nitrogen-rich soils with a pH of between 6.0 and 6.8. Heat generally prompts lettuce to bolt, with most varieties growing poorly above 75 °F (24 °C); cool temperatures prompt better performance, with 60 to 65 °F (16 to 18 °C) being preferred and as low as 45 °F (7 °C) being tolerated.[30] Plants in hot areas that are provided partial shade during the hottest part of the day will bolt more slowly. Temperatures above 80 °F (27 °C) will generally result in poor or non-existent germination of lettuce seeds.[30] After harvest, lettuce lasts the longest when kept at 32 °F (0 °C) and 96 percent humidity. Lettuce quickly degrades when stored with fruit such as apples, pears and bananas that release the ripening agent ethylene gas. The high water content of lettuce (94.9 percent) creates problems when attempting to preserve the plant – it cannot be successfully frozen, canned or dried and must be eaten fresh.</p>

<p>Lettuce varieties will cross with each other, making spacing of 5 to 20 feet (1.5 to 6.1 m) between varieties necessary to prevent contamination when saving seeds. Lettuce will also cross with Lactuca serriola (wild lettuce), with the resulting seeds often producing a plant with tough, bitter leaves. Celtuce, a lettuce variety grown primarily in Asia for its stems, crosses easily with lettuces grown for their leaves.[17] This propensity for crossing, however, has led to breeding programs using closely related species in Lactuca, such as L. serriola, L. saligna, and L. virosa, to broaden the available gene pool. Starting in the 1990s, such programs began to include more distantly related species such as L. tatarica.[32] Seeds keep best when stored in cool conditions, and, unless stored cryogenically, remain viable the longest when stored at −4 °F (−20 °C); they are relatively short lived in storage.</p>

<p>At room temperature, lettuce seeds remain viable for only a few months. However, when newly harvested lettuce seed is stored cryogenically, this life increases to a half-life of 500 years for vaporized nitrogen and 3,400 years for liquid nitrogen; this advantage is lost if seeds are not frozen promptly after harvesting.</p>

<p><strong>Culinary use</strong></p>

<p>As described around 50 AD, lettuce leaves were often cooked and served by the Romans with an oil-and-vinegar dressing; however, smaller leaves were sometimes eaten raw. During the 81–96 AD reign of Domitian, the tradition of serving a lettuce salad before a meal began. Post-Roman Europe continued the tradition of poaching lettuce, mainly with large romaine types, as well as the method of pouring a hot oil and vinegar mixture over the leaves.[9] Today, the majority of lettuce is grown for its leaves, although one type is grown for its stem and one for its seeds, which are made into an oil.[21] Most lettuce is used in salads, either alone or with other greens, vegetables, meats and cheeses. Romaine lettuce is often used for Caesar salads, with a dressing that includes anchovies and eggs. Lettuce leaves can also be found in soups, sandwiches and wraps, while the stems are eaten both raw and cooked.[10] The consumption of lettuce in China developed differently from in Western countries, due to health risks and cultural aversion to eating raw leaves. In that country, "salads" were created from cooked vegetables and served hot or cold. Lettuce was also used in a larger variety of dishes than in Western countries, contributing to a range of dishes including bean curd and meat dishes, soups and stir-frys plain or with other vegetables. Stem lettuce, widely consumed in China, is eaten either raw or cooked, the latter primarily in soups and stir-frys.[44] Lettuce is also used as a primary ingredient in the preparation of lettuce soup.</p>

<p><strong>Nutritional content</strong></p>

<p>Depending on the variety, lettuce is an excellent source (20% of the Daily Value, DV, or higher) of vitamin K (97% DV) and vitamin A (21% DV) (table), with higher concentrations of the provitamin A compound, beta-carotene, found in darker green lettuces, such as Romaine.[31] With the exception of the iceberg variety, lettuce is also a good source (10-19% DV) of folate and iron (table).</p>

<p><strong>Religious and medicinal lore</strong></p>

<p>In addition to its usual purpose as an edible leafy vegetable, lettuce has had a number of uses in ancient (and even some more modern) times as a medicinal herb and religious symbol. For example, ancient Egyptians thought lettuce to be a symbol of sexual prowess[43] and a promoter of love and childbearing in women. The Romans likewise claimed that it increased sexual potency.[52] In contrast, the ancient Greeks connected the plant with male impotency,[9] and served it during funerals (probably due to its role in the myth of Adonis's death), and British women in the 19th century believed it would cause infertility and sterility. Lettuce has mild narcotic properties; it was called "sleepwort" by the Anglo-Saxons because of this attribute, although the cultivated L. sativa has lower levels of the narcotic than its wild cousins.[52] This narcotic effect is a property of two sesquiterpene lactones which are found in the white liquid (latex) in the stems of lettuce,[29] called lactucarium or "lettuce opium".</p>

<p>Lettuce is also eaten as part of the Jewish Passover Seder, where it is considered the optimal choice for use as the bitter herb, which is eaten together with the matzah.</p>

<p>Some American settlers claimed that smallpox could be prevented through the ingestion of lettuce,[52] and an Iranian belief suggested consumption of the seeds when afflicted with typhoid.[53] Folk medicine has also claimed it as a treatment for pain, rheumatism, tension and nervousness, coughs and insanity; scientific evidence of these benefits in humans has not been found. The religious ties of lettuce continue into the present day among the Yazidi people of northern Iraq, who have a religious prohibition against eating the plant.</p>

PL 6 (100 S)

How to Grow a Square...

Price

€0.95

(SKU: HTGSW)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8" />

<div id="idTab1" class="rte">

<h2><strong>How to Grow a Square Watermelon</strong></h2>

<p>Here you can buy and download a PDF manual ( with pictures ) How to Grow a Square Watermelon.<br />Manuals are available following languages:<br />Deutsch <br />English <br />Español <br />France <br />Italiano <br />Português <br />Srpski</p>

</div>

HTGSW

Coming Soon

Nutmeg Seeds - Aphrodisiac...

Price

€4.95

(SKU: T 54)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<div id="idTab1" class="rte">

<h2><strong>Nutmeg Seeds - Aphrodisiac (Myristica Fragrans)</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #f50303;"><strong>Price for Package of 1 or 2 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>The Nutmeg fruit is similar in appearance to an apricot. When fully mature it splits in two, exposing a crimson-colored edible pulp surrounding a single seed, the nutmeg.<</p>

<p>Nutmeg - the spice consisting of the seed has a characteristic, pleasant fragrance and slightly warm taste; it is used to flavor many kinds of baked goods, confections, puddings, meats, sausages, sauces, vegetables, and such beverages as eggnog.</p>

<p> Nutmeg spice comes from the dried endosperm inside the seed of the Nutmeg tree (Myristica fragrans), a member of the myristica family (Myristicaceae).</p>

<p>Nutmeg is not a nut, but the kernel of an apricot-like fruit. Mace is an arillus, a thin leathery tissue between the stone and the pulp; it is bright red to purple when harvested, but after drying changes to amber.</p>

<p> Both spices are strongly aromatic, resinous and warm in taste. Mace is generally said to have a finer aroma than nutmeg, but the difference is small. Nutmeg quickly loses its fragrance when ground; therefore, the necessary amount should be grated from a whole nut immediately before usage.</p>

<p><strong><em><span style="text-decoration: underline;">The red mace will be removed and the nut will not be red but black. The brown seed inside this nut.</span></em></strong></p>

<p><strong>Wikipedia:</strong></p>

<p>The nutmeg tree is any of several species of trees in genus Myristica. The most important commercial species is Myristica fragrans, an evergreen tree indigenous to the Banda Islands in the Moluccas (or Spice Islands) of Indonesia. The nutmeg tree is important for two spices derived from the fruit: nutmeg and mace.[1]</p>

<p>Nutmeg is the seed of the tree, roughly egg-shaped and about 20 to 30 mm (0.8 to 1.2 in) long and 15 to 18 mm (0.6 to 0.7 in) wide, and weighing between 5 and 10 g (0.2 and 0.4 oz) dried, while mace is the dried "lacy" reddish covering or aril of the seed. The first harvest of nutmeg trees takes place 7–9 years after planting, and the trees reach full production after 20 years. Nutmeg is usually used in powdered form. This is the only tropical fruit that is the source of two different spices. Several other commercial products are also produced from the trees, including essential oils, extracted oleoresins, and nutmeg butter (see below).</p>

<p>The common or fragrant nutmeg, Myristica fragrans, native to the Banda Islands of Indonesia, is also grown in Penang Island in Malaysia and the Caribbean, especially in Grenada. It also grows in Kerala, a state in southern India. Other species of nutmeg include Papuan nutmeg M. argentea from New Guinea, and M. malabarica from India.</p>

<p><strong>Botany and cultivation</strong></p>

<p>Nutmeg is a dioecious plant which is propagated sexually and asexually, the latter being the standard. Sexual propagation by seedling yields 50% male seedlings, which are unproductive. As there is no reliable method of determining plant sex before flowering in the sixth to eighth year, and sexual propagation bears inconsistent yields, grafting is the preferred method of propagation. Epicotyl grafting, approach grafting and patch budding have proved successful, epicotyl grafting being the most widely adopted standard. Air-layering, or marcotting, is an alternative, though not preferred, method, because of its low (35-40%) success rate.</p>

<p><strong>Culinary uses</strong></p>

<p>Nutmeg and mace have similar sensory qualities, with nutmeg having a slightly sweeter and mace a more delicate flavour. Mace is often preferred in light dishes for the bright orange, saffron-like hue it imparts. Nutmeg is used for flavouring many dishes, usually in ground or grated form, and is best grated fresh in a nutmeg grater.</p>

<p>In Penang cuisine, dried, shredded nutmeg rind with sugar coating is used as toppings on the uniquely Penang ais kacang. Nutmeg rind is also blended (creating a fresh, green, tangy taste and white colour juice) or boiled (resulting in a much sweeter and brown juice) to make iced nutmeg juice.</p>

<p>In Indian cuisine, nutmeg is used in many sweet as well as savoury dishes (predominantly in Mughlai cuisine). It is also added in small quantities as a medicine for infants. It may also be used in small quantities in garam masala. Ground nutmeg is also smoked in India.[citation needed]</p>

<p>In Indonesian cuisine, nutmeg is used in various dishes, mainly in many soups, such as soto soup, baso soup or Sup Kambing. It is also made as sweets.</p>

<p>In Middle Eastern cuisine, ground nutmeg is often used as a spice for savoury dishes.</p>

<p>In originally European cuisine, nutmeg and mace are used especially in potato dishes and in processed meat products; they are also used in soups, sauces, and baked goods. In Dutch cuisine, nutmeg is added to vegetables such as Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, and string beans. Nutmeg is a traditional ingredient in mulled cider, mulled wine, and eggnog.</p>

<p>Japanese varieties of curry powder include nutmeg as an ingredient.</p>

<p>In the Caribbean, nutmeg is often used in drinks such as the Bushwacker, Painkiller, and Barbados rum punch. Typically, it is just a sprinkle on the top of the drink.</p>

<p>The pericarp (fruit/pod) is used in Grenada and also in Indonesia to make jam, or is finely sliced, cooked with sugar, and crystallised to make a fragrant candy.</p>

<p>In Scotland, mace and nutmeg are usually both essential ingredients in haggis.</p>

<p><strong>Essential oils</strong></p>

<p>The essential oil obtained by steam distillation of ground nutmeg is used widely in the perfumery and pharmaceutical industries. This volatile fraction typically contains 60-80% d-camphene by weight, as well as quantities of d-pinene, limonene, d-borneol, l-terpineol, geraniol, safrol, and myristicin.[5] The oil is colourless or light yellow, and smells and tastes of nutmeg. It contains numerous components of interest to the oleochemical industry, and is used as a natural food flavouring in baked goods, syrups, beverages, and sweets. It is used to replace ground nutmeg, as it leaves no particles in the food. The essential oil is also used in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries, for instance, in toothpaste, and as a major ingredient in some cough syrups. In traditional medicine, nutmeg and nutmeg oil were used for disorders related to the nervous and digestive systems.</p>

<p>After extraction of the essential oil, the remaining seed, containing much less flavour, is called "spent". Spent is often mixed in industrial mills with pure nutmeg to facilitate the milling process, as nutmeg is not easy to mill due to the high percentage of oil in the pure seed. Ground nutmeg with a variable percentage of spent (around 10% w/w) is also less likely to clot. To obtain a better running powder also a small percentage of rice flour can be added.[citation needed]</p>

<p><strong>Nutmeg butter</strong></p>

<p>Nutmeg butter is obtained from the nut by expression. It is semi-solid, reddish brown in colour, and tastes and smells of nutmeg. Approximately 75% (by weight) of nutmeg butter is trimyristin, which can be turned into myristic acid, a 14-carbon fatty acid, which can be used as a replacement for cocoa butter, can be mixed with other fats like cottonseed oil or palm oil, and has applications as an industrial lubricant.</p>

<p><strong>History</strong></p>

<p>It is known to have been a prized costly spice in European medieval cuisine as a flavouring, medicinal, and preservative agent. Saint Theodore the Studite (ca. 758 – ca. 826) allowed his monks to sprinkle nutmeg on their pease pudding when required to eat it. In Elizabethan times, it was believed nutmeg could ward off the plague, so nutmeg became very popular and its price skyrocketed.[6]</p>

<p>The small Banda Islands were, until the mid-19th century, the world's only source of nutmeg and mace. Nutmeg is noted as a very valuable commodity by Muslim sailors from the port of Basra, such as Sinbad the Sailor in the One Thousand and One Nights. Nutmeg was traded by Arabs during the Middle Ages and sold to the Venetians for very high prices, but the traders did not divulge the exact location of their source in the profitable Indian Ocean trade, and no European was able to deduce their location.</p>

<p>In August 1511, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca, which at the time was the hub of Asian trade, on behalf of the king of Portugal. In November of that year, after having secured Malacca and learning of the Bandas' location, Albuquerque sent an expedition of three ships led by his friend António de Abreu to find them. Malay pilots, either recruited or forcibly conscripted, guided them via Java, the Lesser Sundas and Ambon to Banda, arriving in early 1512.[7] The first Europeans to reach the Bandas, the expedition remained in Banda for about a month, purchasing and filling their ships with Banda's nutmeg and mace, and with cloves in which Banda had a thriving entrepôt trade.[8] The first written accounts of Banda are in Suma Oriental, a book written by the Portuguese apothecary Tomé Pires, based in Malacca from 1512 to 1515. Full control of this trade by the Portuguese was not possible, and they remained participants without a foothold in the islands themselves.</p>

<p>The trade in nutmeg later became dominated by the Dutch in the 17th century. The English and Dutch engaged in prolonged struggles to gain control of Run Island, then the only source of nutmeg. At the end of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch gained control of Run, while England controlled New Amsterdam (New York) in North America.</p>

<p>The Dutch waged a bloody war, including the massacre and enslavement of the inhabitants of the island of Banda, just to control nutmeg production in the East Indies in 1621. Thereafter, the Banda Islands were run as a series of plantation estates, with the Dutch mounting annual expeditions in local war-vessels to extirpate nutmeg trees planted elsewhere.</p>

<p>In 1760, the price of nutmeg in London was 85 to 90 shillings per pound, a price kept artificially high by the Dutch voluntarily burning full warehouses of nutmegs in Amsterdam.</p>

<p>As a result of the Dutch interregnum during the Napoleonic Wars, the British took temporary control of the Banda Islands from the Dutch and transplanted nutmeg trees (complete with soil) to Sri Lanka, to Penang, to Bencoolen and to Singapore.[9] However, there is evidence that the tree existed in Sri Lanka prior to this.[10] Thence they were transplanted to their other colonial holdings elsewhere, notably Zanzibar and Grenada. The national flag of Grenada, adopted in 1974, shows a stylised split-open nutmeg fruit. The Dutch however continued to hold control of the spice islands until World War II.</p>

<p>Connecticut gets its nickname ("the Nutmeg State", "Nutmegger") from the legend that some unscrupulous Connecticut traders would whittle "nutmeg" out of wood, creating a "wooden nutmeg" (a term which came to mean any fraud).</p>

<p><strong>World production</strong></p>

<p>World production of nutmeg is estimated to average between 10,000 and 12,000 tonnes (9,800 and 12,000 long tons; 11,000 and 13,000 short tons) per year, with annual world demand estimated at 9,000 tonnes (8,900 long tons; 9,900 short tons); production of mace is estimated at 1,500 to 2,000 tonnes (1,500 to 2,000 long tons; 1,700 to 2,200 short tons). Indonesia and Grenada dominate production and exports of both products, with world market shares of 75% and 20% respectively. Other producers include India, Malaysia (especially Penang, where the trees grow wild within untamed areas[citation needed]), Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka, and Caribbean islands, such as St. Vincent and Grenada, which produces 20% of the world's nutmeg supply. The principal import markets are the European Community, the United States, Japan and India. Singapore and the Netherlands are major re-exporters.</p>

<p><strong>Medical research</strong></p>

<p>Nutmeg has been used in medicine since at least the seventh century. In the 19th century it was used as an abortifacient, which led to numerous recorded cases of nutmeg poisoning. Although used as a folk treatment for other ailments, unprocessed nutmeg has no proven medicinal value today.[12]</p>

<p>One study has shown that the compound macelignan isolated from Myristica fragrans (Myristicaceae) may exert antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus mutans,[13] and another that a methanolic extract from the same plant inhibited Jurkat cell activity in human leukemia,[14] but these are not currently used treatments.</p>

<p>Psychoactivity and toxicity</p>

<p><strong>Effects</strong></p>

<p>In low doses, nutmeg produces no noticeable physiological or neurological response, but in large doses, raw nutmeg has psychoactive effects. In its freshly ground (from whole nutmegs) form, nutmeg contains myristicin, a monoamine oxidase inhibitor and psychoactive substance. Myristicin poisoning can induce convulsions, palpitations, nausea, eventual dehydration, and generalized body pain.[15] It is also reputed to be a strong deliriant.[16]</p>

<p>Fatal myristicin poisonings in humans are very rare, but two have been reported: one in an 8-year-old child[17] and another in a 55-year-old adult, the latter case attributed to a combination with flunitrazepam.</p>

<p>In case reports raw nutmeg produced anticholinergic-like symptoms, attributed to myristicin and elemicin.</p>

<p>In case reports intoxications with nutmeg had effects that varied from person to person, but were often reported to be an excited and confused state with headaches, nausea and dizziness, dry mouth, bloodshot eyes and memory disturbances. Nutmeg was also reported to induce hallucinogenic effects, such as visual distortions and paranoid ideation. In the reports nutmeg intoxication took several hours before maximum effect was reached. Effects and after-effects lasted up to several days.</p>

<p>Myristicin poisoning is potentially deadly to some pets and livestock, and may be caused by culinary quantities of nutmeg harmless to humans. For this reason, it is recommended not to feed eggnog to dogs.[30]</p>

<p><strong>History of use</strong></p>

<p>Peter Stafford's Psychedelics Encyclopedia quotes an 1883 report from Mumbai noting that "the Hindus of West India take nutmeg as an intoxicant", and records that the spice has been used for centuries as a form of snuff in rural eastern Indonesia and India, latter seeing the ground seed mixed with betel and other kinds of snuff. In 1829, the Czech physiologist Jan Evangelista Purkinje ingested three ground nutmegs with a glass of wine and recorded headaches, nausea, hallucinations and a sense of euphoria that lasted for several days.[12]</p>

<p>Harvard ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes and chemist Albert Hofmann, who discovered LSD, documented reports of nutmeg's use as an intoxicant by students, prisoners, sailors, alcoholics and marijuana smokers. In his autobiography, Malcolm X writes about taking nutmeg and other "semi-drugs" while serving time in prison.[12]</p>

<p>The Angewandte Chemie International Edition records the use of nutmeg as an intoxicant in the United States in the post-World War II period, notably among young people, bohemians, and prisoners. A 1966 New York Times piece named it along with morning glory seeds, diet aids, cleaning fluids, cough medicine, and other substances as "alternative highs" on college campuses.[12]</p>

<p><strong>Toxicity during pregnancy</strong></p>

<p>Nutmeg was once considered an abortifacient, but may be safe for culinary use during pregnancy. However, it inhibits prostaglandin production and contains hallucinogens that may affect the fetus if consumed in large quantities.</p>

</div>

T 54 (1S)

Medicinal or spice plant

Plant resistant to cold and frost

PAPER MULBERRY Seeds...

Price

€1.85

(SKU: T 55)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<div id="idTab1" class="rte">

<h2><span style="font-size: 14pt;"><strong>PAPER MULBERRY Seeds (Broussonetia papyrifera)</strong></span></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000; font-size: 14pt;"><strong>Price for Package of 5 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>The paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera, syn. Morus papyrifera L.) is a species of flowering plant in the family Moraceae. It is native to Asia, where its range includes China, Japan, Korea, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Burma, and India. It is widely cultivated elsewhere and it grows as an introduced species in parts of Europe, the United States, and Africa. Other common names include tapa cloth tree.</p>

<p><strong>Description</strong></p>