Menu

-

MenuBack

- Home

-

Categories

-

-

Categories

-

Vegetable Seeds

-

Varieties by Country

- Varieties from Armenia

- Varieties from BiH

- Varieties from Croatia

- Varieties from France

- Varieties from Germany

- Varieties from Greece

- Varieties from Hungary

- Varieties from India

- Varieties from Italy

- Varieties from Japan

- Varieties from North Macedonia

- Varieties from Peru

- Varieties from Russia

- Varieties from Serbia

- Varieties from Slovenia

- Varieties from Spain

- Varieties from Thailand

- Varieties from Turkey

- Varieties from USA

- Tomato Seeds

- Corn Seeds

- Gourd family

- Bean family

- Cucumber Seeds

- Pepper Seeds

- Carrot family

- Onion family

- Lettuce Seeds

- Potato family

- Cabbage family

- Radish Seeds

- Beetroot family

- Watermelon Seeds

- Melon Seeds

- Cauliflower Seeds

- Sunflower family

-

Varieties by Country

- Fruit Seeds

- Chili - Habanero Seeds

- Medicinal Herb Seeds

- Climbing Plants Seeds

- Trees Bonsai Seeds

- Palm Seeds

- Ornamental Grasses Seeds

- Tobacco Seeds

-

Vegetable Seeds

-

-

-

-

- NEW PRODUCTS

- Create account

- Delivery - Payment

- FAQ

- Home

-

- Large Packets of Seeds

- Giant Plants Seeds

- Vegetable Seeds

- Varieties by Country

- Varieties from Armenia

- Varieties from BiH

- Varieties from Croatia

- Varieties from France

- Varieties from Germany

- Varieties from Greece

- Varieties from Hungary

- Varieties from India

- Varieties from Italy

- Varieties from Japan

- Varieties from North Macedonia

- Varieties from Peru

- Varieties from Russia

- Varieties from Serbia

- Varieties from Slovenia

- Varieties from Spain

- Varieties from Thailand

- Varieties from Turkey

- Varieties from USA

- Tomato Seeds

- Corn Seeds

- Gourd family

- Bean family

- Cucumber Seeds

- Pepper Seeds

- Carrot family

- Onion family

- Lettuce Seeds

- Potato family

- Cabbage family

- Radish Seeds

- Beetroot family

- Watermelon Seeds

- Melon Seeds

- Cauliflower Seeds

- Sunflower family

- Varieties by Country

- Fruit Seeds

- Chili - Habanero Seeds

- Medicinal Herb Seeds

- Climbing Plants Seeds

- Trees Bonsai Seeds

- Banana Seeds

- Palm Seeds

- Ornamental Grasses Seeds

- Tobacco Seeds

- Flower Seeds

- Cactus Seeds

- Water plants seeds

- Sowing Instructions

- Fruit and vegetable molds

- Mushroom Mycelium

- Plant Bulbs

- Bamboo seeds

- Ayurveda Plants

- F1 Hybrid Seeds

- Packaging and stuff

- Cold-resistant plants

- Plants Care

- Organic Spices

- Delivery - Payment

- No PayPal and Card payment X

Last Product Reviews

Out of the two seeds, one germinated and the other one was dead and floatin...

By

Riikka H on 07/03/2024

Riikka H on 07/03/2024

Verified Purchase

Best sellers

There are 1316 products.

Showing 61-75 of 1316 item(s)

Mosquito Grass - Blue Grama...

Price

€1.45

(SKU: UT 11)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><span style="font-size:14pt;"><strong>Mosquito Grass - Blue Grama Seeds (Bouteloua Gracilis)</strong></span></h2>

<h2><span style="color:#ff0000;font-size:14pt;"><strong>Price for Package of 10 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Blonde Ambition Blue Grama Grass (Bouteloua gracilis Blonde Ambition) is a native ornamental grass with a completely new look. The horizontal eyelash-like chartreuse flowers appear in mid-summer and age to blonde seed heads by fall. They are held on the plant right through the winter to provide many months of interest.</p>

<p>Plant Select Winner 2011 30-36" tall x 30-36" wide. An exceptionally large growing selection of our native Blue Grama Grass, Bouteloua gracilis Blonde Ambition has 2 1/2 to 3 ft. tall stems of flowers that mature to long lasting blonde seed heads. These flag-like flowers rise up out of the blue-green foliage in mid-summer and are held on stiff, weather resistant stems. 'Blonde Ambition' Blue Grama Grass provides exceptional winter interest as the stems of seed heads pop up even after a heavy snow and remain standing through winter, giving the grass 6 to 8 months of garden color and texture.</p>

<p>Seldom does a new grass selection offer the gardener something so completely different and exciting. Its profusion of big, showy chartreuse flowers, held horizontally above the leaves is unlike any other ornamental grass in cultivation. This beauty is extremely cold hardy, grows in a wide range of soil types and is a perfect choice for low maintenance home or commercial landscapes. 'Blonde Ambition' Grass is native to 26 states and performs well across the country, particularly in hardiness zones 4-9. Cut back old stems to 2-3” above ground-level in mid-spring. Divide every third year. Discovered and introduced by David Salman of High Country Gardens. (Propagated by division).</p>

<p>2011 High Country Gardens Plant of the Year. Blonde Ambition Blue Grama Grass was named by the Plant Select gardeners' survey as the best perennial of 2013.</p>

<p><strong><em>Planting Guides</em></strong></p>

<p>Caring For Blonde Ambition Blue Grama Grass</p>

<p>Cutting back Blonde Ambition Blue Grama Grass (Bouteloua gracilis Blonde Ambition) should be done in mid-spring when the new green grass blades begin to sprout from the crown. The stems holding the seed heads are very resilient and stay upright even after a snowy winter, so the grass looks good until mid-spring.</p>

<p>Cut back to a height of 2 to 3 inches above ground level and scratch out the crown with gloved hands to loosen thatch and make room for the new growth to push up and out.</p>

<p>Mulching: Blonde Ambition (and many ornamental grasses) don't need mulching. But if planted in a mulched bed, Blonde Ambition is very adaptable as to the type of mulch. We recommend that the mulch layer around the plant be thin (less than an inch deep).</p>

<h2>WIKIPEDIA:</h2>

<p>Bouteloua gracilis (blue grama) is a long-lived, warm-season (C4) perennial grass, native to North America.</p>

<p>It is most commonly found from Alberta, Canada, east to Manitoba and south across the Rocky Mountains, Great Plains, and U.S. Midwest states, onto the northern Mexican Plateau in Mexico.</p>

<p>Blue grama accounts for most of the net primary productivity in the shortgrass prairie of the central and southern Great Plains. It is a green or greyish, low-growing, drought-tolerant grass with limited maintenance.</p>

<p>Blue grama grows on a wide array of topographic positions, and in a range of well-drained soil types, from fine to coarse-textured.</p>

<p>Blue grama has green to greyish leaves less than 3 millimetres (0.1 in) wide and 1 to 10 inches (25 to 250 mm) long. The overall height of the plant is 6 to 12 in (15 to 30 cm) at maturity.[3]</p>

<p>The flowering stems (culms) are 7 to 18 inches (18 to 46 cm) long. There are typically two comb-like spikes, each with 20 to 90 spikelets, that extend out at a sharp angle from the flowering stem.</p>

<p>Each spikelet is 5 to 6 mm (0.20 to 0.24 in) long. There is one fertile floret with a lemma (bract) 5 to 5.5 mm (0.20 to 0.22 in) long, with three short awns (bristles) at the tip, and one reduced sterile floret about 2 mm (0.08 in) long with three awns about 5 mm (0.2 in) long.</p>

<p>The roots generally grow 12 to 18 inches (30 to 46 cm) outwards, and 3 to 6.5 feet (0.9 to 2.0 m) deep.</p>

<p>Blue grama is readily established from seed, but depends more on vegetative reproduction via tillers. Seed production is slow, and depends on soil moisture and temperature. Seeds dispersed by wind only reach a few meters (6 ft); farther distances are reached with insects, birds, and mammals as dispersal agents. Seedling establishment, survival, and growth are greatest when isolated from neighboring adult plants, which effectively exploit water in the seedling's root zone. Successful establishment requires a modest amount of soil moisture during the extension and development of adventitious roots.</p>

<p>Established plants are grazing-, cold-, and drought-tolerant, though prolonged drought leads to a reduction in root number and extent. They employ an opportunistic water-use strategy, rapidly using water when available, and becoming dormant during less-favorable conditions. In terms of successional status, blue grama is a late seral to climax species. Recovery following disturbance is slow and depends on the type and extent of the disturbance.</p>

<p><strong>Horticulture and agriculture</strong></p>

<p>Blue grama is valued as forage.</p>

<p>Bouteloua gracilis is grown by the horticulture industry, and used in perennial gardens; naturalistic and native plant landscaping; habitat restoration projects; and in residential, civic, and highway erosion control. Blue Grama flowers are also used in dried flower arrangements.</p>

<p>Blue grama is the state grass of Colorado and New Mexico. It is listed as an endangered species in Illinois.</p>

<p>Among the Zuni people, the grass bunches are tied together and the severed end used as a hairbrush, the other as a broom. Bunches are also used to strain goat's milk.</p>

<p><strong>Garden Uses</strong></p>

<p>Small size makes blue grama grass an excellent selection for rock gardens where it can be used as a specimen or in small groups. Also an excellent choice for naturalized areas, native plant gardens, unmowed meadows, prairie areas or other informal areas in the landscape, especially where drought tolerant plants are needed. Can also be grown as a turf grass and regularly mowed to 2 inches high. Flower spikes are an excellent addition for dried flower arrangements.</p>

<p><strong>Culture</strong></p>

<p>Easily grown in average, dry to medium, well-drained soils in full sun. Tolerates a wide range of soils, except poorly-drained, wet ones. Excellent drought tolerance. Freely self-seeds. Cut to the ground in late winter before new shoots appear.</p>

UT 11

Black Pepper Seeds (Piper...

Price

€1.95

(SKU: MHS 56 PN)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8" />

</head>

<body>

<h2><strong>Black Pepper Seeds (Piper nigrum)</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 5 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Black pepper (Piper nigrum) is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit, which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. When dried, the fruit is known as a peppercorn. When fresh and fully mature, it is approximately 5 millimeters (0.20 in) in diameter, dark red, and, like all drupes, contains a single seed. Peppercorns, and the ground pepper derived from them, maybe described simply as pepper, or more precisely as black pepper (cooked and dried unripe fruit), green pepper (dried unripe fruit) and white pepper (ripe fruit seeds).</p>

<p>Black pepper is native to south India and is extensively cultivated there and elsewhere in tropical regions. Currently, Vietnam is the world's largest producer and exporter of pepper, producing 34% of the world's Piper nigrum crop as of 2013.</p>

<p>Dried ground pepper has been used since antiquity for both its flavor and as traditional medicine. Black pepper is the world's most traded spice. It is one of the most common spices added to cuisines around the world. The spiciness of black pepper is due to the chemical piperine, not to be confused with the capsaicin characteristic of fresh hot peppers. Black pepper is ubiquitous in the modern world as a seasoning and is often paired with salt.</p>

<p><strong>Etymology</strong></p>

<p>The word "pepper" has its roots in the Dravidian word for long pepper, pippali.[2][3][4] Ancient Greek and Latin turned pippali into the Greek πέπερι peperi and then into the Latin piper, which was used by the Romans to refer both to black pepper and long pepper, as the Romans erroneously believed that both of these spices were derived from the same plant.[5] Today's "pepper" derives from the Old English pipor. The Latin word is also the source of Romanian piper, Italian pepe, Dutch peper, German Pfeffer, French poivre, and other similar forms.</p>

<p>In the 16th century, pepper started referring to the unrelated New World chili pepper as well. "Pepper" was used in a figurative sense to mean "spirit" or "energy" at least as far back as the 1840s; in the early 20th century, this was shortened to pep.</p>

<p><strong>Black pepper</strong></p>

<p>Black pepper is produced from the still-green, unripe drupes of the pepper plant. The drupes are cooked briefly in hot water, both to clean them and to prepare them for drying. The heat ruptures cell walls in the pepper, speeding the work of browning enzymes during drying. The drupes are dried in the sun or by machine for several days, during which the pepper around the seed shrinks and darkens into a thin, wrinkled black layer. Once dried, the spice is called black peppercorn. On some estates, the berries are separated from the stem by hand and then sun-dried without the boiling process.</p>

<p>Once the peppercorns are dried, pepper spirit and oil can be extracted from the berries by crushing them. Pepper spirit is used in many medicinal and beauty products. Pepper oil is also used as an ayurvedic massage oil and used in certain beauty and herbal treatments.</p>

<p><strong>Plant</strong></p>

<p>The pepper plant is a perennial woody vine growing up to 4 meters (13 ft) in height on supporting trees, poles, or trellises. It is a spreading vine, rooting readily where trailing stems touch the ground. The leaves are alternate, entire, 5 to 10 centimetres (2.0 to 3.9 in) long and 3 to 6 centimetres (1.2 to 2.4 in) across. The flowers are small, produced on pendulous spikes 4 to 8 centimetres (1.6 to 3.1 in) long at the leaf nodes, the spikes lengthening up to 7 to 15 centimetres (2.8 to 5.9 in) as the fruit matures.[15] The fruit of the black pepper is called a drupe and when dried is known as a peppercorn.</p>

<p>Pepper can be grown in soil that is neither too dry nor susceptible to flooding, moist, well-drained and rich in organic matter (the vines do not do too well over an altitude of 900 m (3,000 ft) above sea level). The plants are propagated by cuttings about 40 to 50 centimetres (16 to 20 in) long, tied up to neighbouring trees or climbing frames at distances of about 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) apart; trees with rough bark are favoured over those with smooth bark, as the pepper plants climb rough bark more readily. Competing plants are cleared away, leaving only sufficient trees to provide shade and permit free ventilation. The roots are covered in leaf mulch and manure, and the shoots are trimmed twice a year. On dry soils the young plants require watering every other day during the dry season for the first three years. The plants bear fruit from the fourth or fifth year, and typically continue to bear fruit for seven years. The cuttings are usually cultivars, selected both for yield and quality of fruit.</p>

<p>A single stem will bear 20 to 30 fruiting spikes. The harvest begins as soon as one or two fruits at the base of the spikes begin to turn red, and before the fruit is fully mature, and still hard; if allowed to ripen completely, the fruit lose pungency, and ultimately fall off and are lost. The spikes are collected and spread out to dry in the sun, then the peppercorns are stripped off the spikes.[15]</p>

<p>Black pepper is either native to Southeast Asia[16] or South Asia.[17] Within the genus Piper, it is most closely related to other Asian species such as Piper caninum.</p>

<p><strong>History</strong></p>

<p>Pepper is native to South Asia and Southeast Asia and has been known to Indian cooking since at least 2000 BCE.[20] J. Innes Miller notes that while pepper was grown in southern Thailand and in Malaysia, its most important source was India, particularly the Malabar Coast, in what is now the state of Kerala[21] Peppercorns were a much-prized trade good, often referred to as "black gold" and used as a form of commodity money. The legacy of this trade remains in some Western legal systems which recognize the term "peppercorn rent" as a form of a token payment made for something that is in fact being given.</p>

<p>The ancient history of black pepper is often interlinked with (and confused with) that of long pepper, the dried fruit of closely related Piper longum. The Romans knew of both and often referred to either as just "piper". In fact, it was not until the discovery of the New World and of chili peppers that the popularity of long pepper entirely declined. Chili peppers, some of which when dried are similar in shape and taste to long pepper, were easier to grow in a variety of locations more convenient to Europe.</p>

<p>Before the 16th century, pepper was being grown in Java, Sunda, Sumatra, Madagascar, Malaysia, and everywhere in Southeast Asia. These areas traded mainly with China, or used the pepper locally.[22] Ports in the Malabar area also served as a stop-off point for much of the trade in other spices from farther east in the Indian Ocean. Following the British hegemony in India, virtually all of the black pepper found in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa was traded from Malabar region.</p>

<p><strong>Ancient times</strong></p>

<p>Black peppercorns were found stuffed in the nostrils of Ramesses II, placed there as part of the mummification rituals shortly after his death in 1213 BCE.[23] Little else is known about the use of pepper in ancient Egypt and how it reached the Nile from South Asia.</p>

<p>Pepper (both long and black) was known in Greece at least as early as the 4th century BCE, though it was probably an uncommon and expensive item that only the very rich could afford. Trade routes of the time were by land, or in ships which hugged the coastlines of the Arabian Sea. Long pepper, growing in the north-western part of India, was more accessible than the black pepper from further south; this trade advantage, plus long pepper's greater spiciness, probably made black pepper less popular at the time.</p>

<p>By the time of the early Roman Empire, especially after Rome's conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, open-ocean crossing of the Arabian Sea direct to southern India's Malabar Coast was near routine. Details of this trading across the Indian Ocean have been passed down in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. According to the Roman geographer Strabo, the early Empire sent a fleet of around 120 ships on an annual one-year trip to China, Southeast Asia, India and back. The fleet timed its travel across the Arabian Sea to take advantage of the predictable monsoon winds. Returning from India, the ships travelled up the Red Sea, from where the cargo was carried overland or via the Nile-Red Sea canal to the Nile River, barged to Alexandria, and shipped from there to Italy and Rome. The rough geographical outlines of this same trade route would dominate the pepper trade into Europe for a millennium and a half to come.</p>

<p>With ships sailing directly to the Malabar coast, black pepper was now travelling a shorter trade route than long pepper, and the prices reflected it. Pliny the Elder's Natural History tells us the prices in Rome around 77 CE: "Long pepper ... is fifteen denarii per pound, while that of white pepper is seven, and of black, four." Pliny also complains "there is no year in which India does not drain the Roman Empire of fifty million sesterces," and further moralizes on pepper:</p>

<p> It is quite surprising that the use of pepper has come so much into fashion, seeing that in other substances which we use, it is sometimes their sweetness, and sometimes their appearance that has attracted our notice; whereas, pepper has nothing in it that can plead as a recommendation to either fruit or berry, its only desirable quality being a certain pungency; and yet it is for this that we import it all the way from India! Who was the first to make trial of it as an article of food? and who, I wonder, was the man that was not content to prepare himself by hunger only for the satisfying of a greedy appetite?</p>

<p>Black pepper was a well-known and widespread, if expensive, seasoning in the Roman Empire. Apicius' De re coquinaria, a 3rd-century cookbook probably based at least partly on one from the 1st century CE, includes pepper in a majority of its recipes. Edward Gibbon wrote, in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, that pepper was "a favorite ingredient of the most expensive Roman cookery".</p>

<p><strong>Phytochemicals, folk medicine, and research</strong></p>

<p>Like many eastern spices, pepper was historically both a seasoning and a folk medicine. Long pepper, being stronger, was often the preferred medication, but both were used. Black pepper (or perhaps long pepper) was believed to cure several illnesses, such as constipation, insomnia, oral abscesses, sunburn and toothaches, among others.[35] Various sources from the 5th century onward recommended pepper to treat eye problems, often by applying salves or poultices made with pepper directly to the eye. There is no current medical evidence that any of these treatments has any benefit.</p>

<p>Pepper is known to cause sneezing. Some sources say that piperine, a substance present in black pepper, irritates the nostrils, causing the sneezing.[37] Few, if any, controlled studies have been carried out to answer the question.</p>

<p>Piperine is under study for its potential to increase absorption of selenium, vitamin B, beta-carotene and curcumin, as well as other compounds.[38] As a folk medicine, pepper appears in the Buddhist Samaññaphala Sutta, chapter five, as one of the few medicines allowed to be carried by a monk.[39] Pepper contains phytochemicals,[40] including amides, piperidines, pyrrolidines and trace amounts of safrole which may be carcinogenic in laboratory rodents.</p>

<p>Piperine is under study for a variety of possible physiological effects,[42] although this work is preliminary and mechanisms of activity for piperine in the human body remain unknown.</p>

<p><strong>Nutrition</strong></p>

<p>One tablespoon (6 grams) of ground black pepper contains moderate amounts of vitamin K (13% of the daily value or DV), iron (10% DV) and manganese (18% DV), with trace amounts of other essential nutrients, protein and dietary fibre.</p>

<p><strong>Flavor</strong></p>

<p>Pepper gets its spicy heat mostly from piperine derived both from the outer fruit and the seed. Black pepper contains between 4.6% and 9.7% piperine by mass, and white pepper slightly more than that.[44] Refined piperine, by weight, is about one percent as hot as the capsaicin found in chili peppers.[45] The outer fruit layer, left on black pepper, also contains important odour-contributing terpenes including pinene, sabinene, limonene, caryophyllene, and linalool, which give citrusy, woody, and floral notes. These scents are mostly missing in white pepper, which is stripped of the fruit layer. White pepper can gain some different odours (including musty notes) from its longer fermentation stage.[46] The aroma of pepper is attributed to rotundone (3,4,5,6,7,8-Hexahydro-3α,8α-dimethyl-5α-(1-methylethenyl)azulene-1(2H)-one), a sesquiterpene originally discovered in the tubers of cyperus rotundus, which can be detected in concentrations of 0.4 nanograms/L in water and in wine: rotundone is also present in marjoram, oregano, rosemary, basil, thyme, and geranium, as well as in some Shiraz wines.</p>

<p>Pepper loses flavour and aroma through evaporation, so airtight storage helps preserve its spiciness longer. Pepper can also lose flavour when exposed to light, which can transform piperine into nearly tasteless isochavicine. Once ground, pepper's aromatics can evaporate quickly; most culinary sources recommend grinding whole peppercorns immediately before use for this reason. Handheld pepper mills or grinders, which mechanically grind or crush whole peppercorns, are used for this, sometimes instead of pepper shakers that dispense pre-ground pepper. Spice mills such as pepper mills were found in European kitchens as early as the 14th century, but the mortar and pestle used earlier for crushing pepper have remained a popular method for centuries as well.</p>

</body>

</html>

MHS 56 PN

Yellow Watermelon Seeds...

Price

€2.15

(SKU: V 255)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><span style="color: #000000;"><strong>Yellow Watermelon Seeds JANOSIK</strong></span></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;" class=""><strong>Price for Package of 20 (1.2g) seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>A very unusual and highly prized Polish yellow-fleshed melon variety is delicious and different. Janosik watermelon comes to us from Poland, it is named in honor of a folklore hero, a Robin Hood type of character. It is one of the very best yellow watermelons, with extra sweet, yellow flesh, never mealy, very high sugar content and very productive. Melons are generally round, though some may be more oval.</p>

<p>Weight averages 4 - 6 kg with each plant producing two to three melons.</p><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

V 255 (20 S)

Variety from Hungary

Sweet Pepper Seeds Soroksari

Price

€1.95

(SKU: PP 63)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2 class=""><strong>Sweet Pepper Seeds Soroksari</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for pack of 50 (1 g) seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<div>Soroksari variety from Hungary is one of the best mid-early varieties of sweet pepper. The fruits are clustered, massive, square, with three or four margins at the apex. 8-9 cm in length and 6-7 cm in diameter are light yellows in technological maturity and light red in physiological maturity. Meat thickness is 5 to 7 mm. It is very fertile and grateful for cultivation in the open field.</div>

<script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

PP 63 (50 S)

Giant plant (with giant fruits)

Giant Watermelon Seeds

Price

€6.00

(SKU: VE 117 G)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>Giant Watermelon Seeds</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;" class=""><strong>Price for Package of 40+ (2g) seeds.</strong></span></h2>

A very productive variety producing large melons weight up to 150 kg. The fruit has very sweet flesh that is brilliant red. Good disease resistance.<br><br>Our selected and tested seeds produce oblong watermelons with light green streaks, with a delicious and very sweet taste and a jaw-dropping size, even from the Guinness Book of Records. The weight, if grown carefully, can exceed 130 kilograms.<br><br>Giant watermelons need warm, moist, well-drained soil. It should be remembered to place the plants at least two meters from each other by virtue of the size that the Giant Watermelon can reach. <br><br>Choose an always sunny place in the garden, for the best results.<script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

VE 117 G (2g)

Plant resistant to cold and frost

Maqui or Chilean Wineberry...

Price

€2.85

(SKU: V 237)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8" />

</head>

<body>

<h2><strong>Maqui or Chilean Wineberry Seeds (Aristotelia chilensis)</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 5 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p><span>Maqui is an amazing anti-oxidant fruit from Chile. Its sweet fruit carries more antioxidants than blueberries and even açai.<span> </span>It grows in a wide range of climates and is very versatile for this.<span> </span>Commercial maqui production is just starting out as the amazing health benefits of this fruit are learned about around the world.</span></p>

<p><span>In ancient times, Indigenous peoples would make an alcoholic beverage from the sweet pulp. Today in Chile it is enjoyed by vacationers in the Patagonia region. It's an easy shrub to spot in high humidity areas or near streams.<span> </span></span></p>

<p><span><span> </span>Germination is from a couple of weeks to 3 months.<span> </span></span></p>

<p><strong><span>Instructions</span></strong><span>: Seeds can be soaked in water for 24 hours. Plant seeds in a moist medium.<span> </span>Sphagnum moss works well. Keep at warm temps for several weeks. Do not oversaturate the medium.<span> </span>We have lower shipping if you purchase multiple packets and more seeds at our acai site.<span> </span>Also, it can speed up germination to scratch the seed coat with sandpaper.</span></p>

<h2><span>WIKIPEDIA:</span></h2>

<p><span>Aristotelia chilensis, the maqui or Chilean wineberry, is a species of the Elaeocarpaceae family native to the Valdivian temperate rainforests of Chile and adjacent regions of southern Argentina. Maqui is sparsely cultivated.</span></p>

<p><span>Maqui is a small dioecious tree reaching 4–5 m in height and is evergreen. Its divided trunk has a smooth bark. The branches are abundant, thin and flexible. The leaves are simple, opposite, hanging, oval-lanceolate, with serrated edges, naked and coriaceous. The leaf venation is well visible and the leaf stalk is strong red. In the beginning of spring, the tree sheds the old cohort. The old cohort is used as a carbohydrate source to form the new leaves and flowers.</span></p>

<h2><strong><span>Flowers and berries</span></strong></h2>

<p><span>Maqui flowers at the end of spring. The white flowers are unisexual and small. They yield a small edible fruit. A tree at the age of seven years produces up to 10 kg berries per year. The small, purple-black berries are approximately 4–6 mm in diameter and contain 4-8 angled seeds. With a taste similar to blackberries, maqui is also known as the Chilean wineberry, and locally in Spanish as maqui or maque.</span></p>

<h2><strong><span>Wild maqui</span></strong></h2>

<p><span>The main area of wild maqui can be found in the Chilean forests. It includes the Coquimbo and Aysén regions and is 170,000 hectares in total area.[2] The average area yield is about 220 kg per hectare annually, with estimated yield of only 90 tons due to its remote access and difficulty for transportation.</span></p>

<h2><strong><span>Harvesting</span></strong></h2>

<p><span>The berries are collected from December to March each year by families, mainly Mapuche who collect their harvest near the Andes Mountains. The process involves collecting the side branches of trees, shaking them to separate the berries, and then employing a mechanical process to separate berries from leaves. The stored fruits are sold in local markets, with prices ranging from US $0.65-1.50 per 100 grams.</span></p>

<h2><strong><span>Seed distribution</span></strong></h2>

<p><span>Maqui berries are a favored food for birds at the end of summer. Deforestation of the Valdivian temperate rainforests in Chile suppresses seed dispersal by birds and leads to inbreeding depression.</span></p>

<h2><strong><span>Cultivation</span></strong></h2>

<p><span>Maqui is planted in home gardens and is not grown on an orchard scale. Most of the fruits on the market come from the wild. Maqui is frost sensitive and fairly tolerant of maritime exposure. It prefers a well-drained soil in full sun with a protection against cold drying winds. The soil should be slightly acidic with moderate fertility.</span></p>

<p><span>Maqui can be planted in USDA- zone 8 to 12. It is cultivated in Spain and in milder, moister areas of Britain where winter frosts reduce plant stock, stimulating growth of more shoots in spring.</span></p>

<h2><strong><span>Propagation</span></strong></h2>

<p><span>The seeds germinate without cold stratification. In zones with the possible appearance of frost, it is recommended to sow in spring in a greenhouse. The plants are planted in autumn into individual pots if they are grown enough. The pots are still in the greenhouse for the first winter.</span></p>

<p><span>After the last expected frost in spring, the plants can be planted out into their final positions. In their first winter outdoors, a frost protection is required.[6] For further propagation, a vegetal reproduction is possible: cuttings of wood with a length of 15 to 30 cm can be planted into pots. These cuttings normally root and can be planted out in the following spring.</span></p>

<h2><strong><span>Uses</span></strong></h2>

<p><span>Maqui berries are used for food and dietary supplements, mainly due to interest for color and anthocyanin content. The berries are raw, dried or processed into jam, juice, an astringent or as an ingredient in processed foods or beverages.</span></p>

<h2><strong><span>Anthocyanin research</span></strong></h2>

<p><span>Only limited polyphenol research has been completed on the maqui berry showing its anthocyanin content to include eight glucoside pigments of delphinidin and cyanidin, the principal anthocyanin being delphinidin 3-sambubioside-5-glucoside (34% of total anthocyanins).[8][9] The average total anthocyanin content was 138 mg per 100 g of fresh fruit (212 mg per 100 g of dry fruit),[9] ranking maqui low among darkly pigmented fruits for anthocyanin content (see Anthocyanins for tabulated content data). One study found that anthocyanins are also present in maqui leaves.</span></p>

<h2><strong><span>History</span></strong></h2>

<p><span>The edible fruit was eaten by the Mapuche Indians. Claude Gay documented in 1844 in his "Physical Atlas of History and Politics of Chile" that natives used maqui to prepare chicha which purportedly contributed unusual strength and stamina for warriors. By speculation, the Mapuche Indians used berry leaves, stems, fruit and wine medicinally over generations.</span></p>

<p><span> </span></p>

</body>

</html>

V 237

Variety from Turkey

Pistachio Seeds (Pistacia...

Price

€1.65

(SKU: V 187 T)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>Pistachio Seeds (Pistacia vera) (Antep Pistachio)</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 5, 20, 50, 100, 500 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Gaziantep, informally called Antep, is a city in southeast Turkey and is among the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world. The Turkish word for pistachio is Antep Fistigi. The Gaziantep area with its fertile soil and arrid climate is the primary growing region for the Antep Pistachio. Many connoisseurs consider this nut to be one of the finest and best tasting nut in the world.</p>

<p><strong>NUTRITIONAL INFORMATION:</strong></p>

<p>Compared to other pistachio varieties including California grown</p>

<p>GENUINE GAZIANTEP PISTACHIOS CONTAIN:</p>

<p>50% less fat</p>

<p>40% less carbohydrates</p>

<p>200% more vitamin C</p>

<p>70% more iron</p>

<p>20% more calcium</p>

<p> 23% more magnesium</p>

<h2>Wikipedia:</h2>

<p>The pistachio (/pɪˈstɑːʃiˌoʊ, -ˈstæ-/,[1] Pistacia vera), a member of the cashew family, is a small tree originating from Central Asia and the Middle East.[2] The tree produces seeds that are widely consumed as food.</p>

<p>Pistacia vera often is confused with other species in the genus Pistacia that are also known as pistachio. These other species can be distinguished by their geographic distributions (in the wild) and their seeds which are much smaller and have a soft shell.</p>

<p><strong>History</strong></p>

<p>Archaeology shows that pistachio seeds were a common food as early as 6750 BC.[3] Pliny the Elder writes in his Natural History that pistacia, "well known among us", was one of the trees unique to Syria, and that the seed was introduced into Italy by the Roman Proconsul in Syria, Lucius Vitellius the Elder (in office in 35 AD) and into Hispania at the same time by Flaccus Pompeius.[4] The early sixth-century manuscript De observatione ciborum ("On the observance of foods") by Anthimus implies that pistacia remained well known in Europe in Late Antiquity. Archaeologists have found evidence from excavations at Jarmo in northeastern Iraq for the consumption of Atlantic pistachio.[3] The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were said to have contained pistachio trees during the reign of King Merodach-Baladan about 700 BC.</p>

<p>The modern pistachio P. vera was first cultivated in Bronze Age Central Asia, where the earliest example is from Djarkutan, modern Uzbekistan.[5][6] It appears in Dioscurides as pistakia πιστάκια, recognizable as P. vera by its comparison to pine nuts.</p>

<p>Additionally, remains of the Atlantic pistachio and pistachio seed along with nut-cracking tools were discovered by archaeologists at the Gesher Benot Ya'aqov site in Israel's Hula Valley, dated to 780,000 years ago.[8] More recently, the pistachio has been cultivated commercially in many parts of the English-speaking world, in Australia, and in New Mexico[9] and California, of the United States, where it was introduced in 1854 as a garden tree.[10] David Fairchild of the United States Department of Agriculture introduced hardier cultivars collected in China to California in 1904 and 1905, but it was not promoted as a commercial crop until 1929.[9][11] Walter T. Swingle’s pistachios from Syria had already fruited well at Niles by 1917.</p>

<p>The earliest records of pistachio in English are around roughly year 1400, with the spellings "pistace" and "pistacia". The word pistachio comes from medieval Italian pistacchio, which is from classical Latin pistacium, which is from ancient Greek pistákion and pistákē, which is generally believed to be from Middle Persian, although unattested in Middle Persian. Later in Persian, the word is attested as pesteh. As mentioned, the tree came to the ancient Greeks from Western Asia.</p>

<p><strong>Habitat</strong></p>

<p>Pistachio is a desert plant, and is highly tolerant of saline soil. It has been reported to grow well when irrigated with water having 3,000–4,000 ppm of soluble salts.[9] Pistachio trees are fairly hardy in the right conditions, and can survive temperatures ranging between −10 °C (14 °F) in winter and 48 °C (118 °F) in summer. They need a sunny position and well-drained soil. Pistachio trees do poorly in conditions of high humidity, and are susceptible to root rot in winter if they get too much water and the soil is not sufficiently free-draining. Long, hot summers are required for proper ripening of the fruit. They have been known to thrive in warm, moist environments.</p>

<p>The Jylgyndy Forest Reserve, a preserve protecting the native habitat of Pistacia vera groves, is located in the Nooken District of Jalal-Abad Province of Kyrgyzstan.</p>

<p><strong>Characteristics</strong></p>

<p>The bush grows up to 10 m (33 ft) tall. It has deciduous pinnate leaves 10–20 centimeters (4–8 inches) long. The plants are dioecious, with separate male and female trees. The flowers are apetalous and unisexual, and borne in panicles.</p>

<p>The fruit is a drupe, containing an elongated seed, which is the edible portion. The seed, commonly thought of as a nut, is a culinary nut, not a botanical nut. The fruit has a hard, creamish exterior shell. The seed has a mauvish skin and light green flesh, with a distinctive flavor. When the fruit ripens, the shell changes from green to an autumnal yellow/red, and abruptly splits part way open (see photo). This is known as dehiscence, and happens with an audible pop. The splitting open is a trait that has been selected by humans.[14] Commercial cultivars vary in how consistently they split open.</p>

<p>Each pistachio tree averages around 50 kilograms (110 lb) of seeds, or around 50,000, every two years.</p>

<p>The shell of the pistachio is naturally a beige color, but it is sometimes dyed red or green in commercial pistachios. Originally, dye was applied by importers to hide stains on the shells caused when the seeds were picked by hand. Most pistachios are now picked by machine and the shells remain unstained, making dyeing unnecessary except to meet ingrained consumer expectations. Roasted pistachio seeds can be artificially turned red if they are marinated prior to roasting in a salt and strawberry marinade, or salt and citrus salts.</p>

<p>Like other members of the Anacardiaceae family (which includes poison ivy, sumac, mango, and cashew), pistachios contain urushiol, an irritant that can cause allergic reactions.</p>

<p><strong>Production and cultivation</strong></p>

<p>Iran, the United States and Turkey are the major producers of pistachios, together accounting for 83% of the world production in 2013 (table).</p>

<p><strong>Cultivation</strong></p>

<p>The trees are planted in orchards, and take approximately seven to ten years to reach significant production. Production is alternate-bearing or biennial-bearing, meaning the harvest is heavier in alternate years. Peak production is reached around 20 years. Trees are usually pruned to size to make the harvest easier. One male tree produces enough pollen for eight to 12 drupe-bearing females. Harvesting in the United States and in Greece is often accomplished using equipment to shake the drupes off the tree. After hulling and drying, pistachios are sorted according to open-mouth and closed-mouth shells. Sun-drying has been found to be the best method of drying,[18] then they are roasted or processed by special machines to produce pistachio kernels.</p>

<p>Pistachio trees are vulnerable to a wide variety of diseases. Among these is infection by the fungus Botryosphaeria, which causes panicle and shoot blight (symptoms include death of the flowers and young shoots), and can damage entire pistachio orchards.</p>

<p>In Greece, the cultivated type of pistachios has an almost-white shell, sweet taste, a red-green kernel and a closed-mouth shell relative to the 'Kerman' variety. Most of the production in Greece comes from the island of Aegina, the region of Thessaly-Almyros and the regional units of West Attica, Corinthia and Phthiotis.</p>

<p>In California, almost all female pistachio trees are the cultivar 'Kerman'. A scion from a mature female 'Kerman' is grafted onto a one-year-old rootstock.</p>

<p>Bulk container shipments of pistachio kernels are prone to self-heating and spontaneous combustion because of their high fat and low water contents.</p>

<p><strong>Consumption</strong></p>

<p>The kernels are often eaten whole, either fresh or roasted and salted, and are also used in pistachio ice cream, kulfi, spumoni, historically in Neapolitan ice cream, pistachio butter,[21][22] pistachio paste[23] and confections such as baklava, pistachio chocolate,[24] pistachio halva,[25] pistachio lokum or biscotti and cold cuts such as mortadella. Americans make pistachio salad, which includes fresh pistachios or pistachio pudding, whipped cream, and canned fruit.</p>

<p>China is the top pistachio consumer worldwide, with annual consumption of 80,000 tons, while the United States consumes 45,000 tons.</p>

<p><strong>Nutritional information</strong></p>

<p>Pistachios are a nutritionally dense food. In a 100 gram serving, pistachios provide 562 calories and are a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value or DV) of protein, dietary fiber, several dietary minerals and the B vitamins, thiamin and especially vitamin B6 at 131% DV (table).[28] Pistachios are a good source (10–19% DV) of calcium, riboflavin, vitamin B5, folate, vitamin E , and vitamin K (table).</p>

<p>The fat profile of raw pistachios consists of saturated fats, monounsaturated fats and polyunsaturated fats.[28][29] Saturated fatty acids include palmitic acid (10% of total) and stearic acid (2%).[29] Oleic acid is the most common monounsaturated fatty acid (51% of total fat)[29] and linoleic acid, a polyunsaturated fatty acid, is 31% of total fat.[28] Relative to other tree nuts, pistachios have a lower amount of fat and calories but higher amounts of potassium, vitamin K, γ-tocopherol, and certain phytochemicals such as carotenoids and phytosterols.</p>

<p><strong>Research and health effects</strong></p>

<p>In July 2003, the United States' Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first qualified health claim specific to seeds lowering the risk of heart disease: "Scientific evidence suggests but does not prove that eating 1.5 ounces (42.5 g) per day of most nuts, such as pistachios, as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of heart disease".[31] Although pistachios contain many calories, epidemiologic studies have provided strong evidence that their consumption is not associated with weight gain or obesity.</p>

<p>A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials concluded that pistachio consumption in persons without diabetes mellitus appears to modestly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure.[32] Several mechanisms for pistachios' antihypertensive properties have been proposed. These mechanisms include pistachios' high levels of the amino acid arginine (a precursor of the blood vessel dilating compound nitric oxide); high levels of phytosterols and monounsaturated fatty acids; and improvement of endothelial cell function through multiple mechanisms including reductions in circulating levels of oxidized low density lipoprotein cholesterol and pro-inflammatory chemical signals.</p>

<p><strong>Toxin and safety concerns</strong></p>

<p>As with other tree seeds, aflatoxin is found in poorly harvested or processed pistachios. Aflatoxins are potent carcinogenic chemicals produced by molds such as Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. The mold contamination may occur from soil, poor storage, and spread by pests. High levels of mold growth typically appear as gray to black filament-like growth. It is unsafe to eat mold-infected and aflatoxin-contaminated pistachios.[33] Aflatoxin contamination is a frequent risk, particularly in warmer and humid environments. Food contaminated with aflatoxins has been found as the cause of frequent outbreaks of acute illnesses in parts of the world. In some cases, such as Kenya, this has led to several deaths.</p>

<p>Pistachio shells typically split naturally prior to harvest, with a hull covering the intact seeds. The hull protects the kernel from invasion by molds and insects, but this hull protection can be damaged in the orchard by poor orchard management practices, by birds, or after harvest, which makes it much easier for pistachios to be exposed to contamination. Some pistachios undergo so-called "early split", wherein both the hull and the shell split. Damage or early splits can lead to aflatoxin contamination.[35] In some cases, a harvest may be treated to keep contamination below strict food safety thresholds; in other cases, an entire batch of pistachios must be destroyed because of aflatoxin contamination. In September 1997, the European Union placed its first ban on pistachio imports from Iran due to high levels of aflatoxin. The ban was lifted in December 1997 after Iran introduced and improved food safety inspections and product quality.</p>

<p>Pistachio shells may be helpful in cleaning up pollution created by mercury emissions.</p><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

V 187 T 5 S

Variety from Russia

Black Plum Tomato Seeds

Price

€1.55

(SKU: VT 49)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<div id="idTab1" class="rte">

<h2 class=""><strong>Black Plum Tomato Seeds</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of<strong> 5, 10, 50 </strong>seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Tomato 'Black Plum' is a Russian commercial variety. The plants are extremely heavy croppers, producing tons of sweet, elongated, mahogany-hued, fat fruits. It is a robust and trouble free variety that in suitable for growing in the greenhouse or outdoors.</p>

<p>The word 'black' when applied to tomatoes can refer to anything from russet-red to smoky purple, dependent on the weather. In the case of Black Plum it's more of a chestnut red with green flambéed shoulders. A gorgeous sight when the plant is hung heavily with clusters of the pretty fruit.</p>

<p> </p>

<p>The elongated large plum-shaped fruits grows to around 8cm (3in) and has the most intense, complex tomato flavour; deep, rich, smoky sweetness, with a tangy aftertaste. Outstanding eaten fresh, cooked in sauces or paste, or dried.</p>

<p>Because of its thick flesh and mild flavour it's good at adding substance and big tomatoey chunks to a dish. It imparts a slightly dusky hue to sauces.Indeterminate they mature in 75 to 82 days.</p>

<h3><strong>Timing:</strong></h3>

<p><strong> </strong>As they cannot tolerate any degree of frost the timing for sowing and planting outside is key to successfully growing tomatoes. Where the seeds are sown under cover or indoors, aim to sow the seeds so that they reach the stage to be transplanted outside three weeks after the last frost date. Tomato plants take roughly seven weeks from sowing to reach the transplanting stage. For example, if your last frost date is early May, the seeds should be planted in early April to allow transplanting at the end of May.</p>

<h3><strong>Position:</strong></h3>

<p><strong> </strong>Tomatoes require a full sun position. Two or three weeks before planting, dig the soil over and incorporate as much organic matter as possible.<br>The best soil used for containers is half potting compost and half a soil-based type loam: this gives some weight to the soil.</p>

<h3><strong>Sowing:</strong></h3>

<p><strong> </strong>Plant about 3mm (1/8in) deep, in small pots using seed starting compost. Water lightly and keep consistently moist until germination occurs. Tomato seeds usually germinate within 5 to 10 days when kept in the optimum temperature range of 21 to 27°C (70 to 80°F). As soon as they emerge, place them in a location that receives a lot of light and a cooler temperature (60 to 70°F); a south-facing window should work.</p>

<h3><strong>Transplanting:</strong></h3>

<p><strong> </strong>When the plants develop their first true leaves, and before they become root bound, they should be transplanted into larger into 20cm (4in) pots. Young plants are very tender and susceptible to frost damage, as well as sunburn. I protect my young plants by placing a large plastic milk jug, with the bottom removed, to form a miniature greenhouse.<br>Depending on the components of your compost, you may need to begin fertilising. If you do fertilise, do it very, very sparingly with a weak dilution. Transplant into their final positions when they are about 15cm (6in) high. Two to three weeks prior to this, the plants should be hardened off.</p>

<h3><strong>Planting:</strong></h3>

<p><strong> </strong>Just before transplanting the tomato plants to their final position drive a strong stake into the ground 5cm (2in) from the planting position. The stake should be at least 30cm (1ft) deep in the ground and 1.2m (4ft) above ground level - the further into the ground the better the support. As the plant grows, tie in the main stem to the support stake - check previous ties to ensure that they do not cut into the stem as the plant grows. Dig a hole 45cm (18in) apart in the bed to the same depth as the pot and water if conditions are at all dry. Ease the plant out of the pot, keeping the root ball as undisturbed as far as possible. Place it in the hole and fill around the plant with soil. The soil should be a little higher than it was in the pot. Loosely tie the plant's stem to the support stake using soft garden twine –allow some slack for future growth.</p>

<h3><strong>Cultivation:</strong></h3>

<p><strong> </strong>A constant supply of moisture is essential, dry periods significantly increase the risk of the fruit splitting. Feed with a liquid tomato fertiliser (high in potash) starting when the first fruits start to form, and every two or three weeks up to the end of August. In September, feed with a general fertiliser (higher in nitrogen) in order to help the plant support it's foliage. Over watering may help to produce larger fruit, but flavour may be reduced. Additionally, splitting and cracking can result from uneven and excessive watering.</p>

<h3><strong>Pruning:</strong></h3>

<p><strong> </strong>When the first fruits begin to form, pinch out the side shoots between the main stem. Also remove lower leaves which show any signs of yellowing to avoid infection.</p>

<h3><strong>Harvesting:</strong></h3>

<p><strong> </strong>Pick as soon as the fruits are ripe, this also encourages the production of more fruit. Harvest all the fruit as soon as frost threatens and ripen on a window sill.</p>

<h3><strong>Black Tomatoes:</strong></h3>

<p><strong> </strong>Black Tomatoes are native to the Southern Ukraine and their seeds were later distributed throughout Western Russia after the Crimean War by soldiers returning home from the front during the early 19th century. <br>Though black tomatoes originally existed in only a relatively small area on the Crimean Peninsula and were limited to only a handful of recognisable varieties, in the years to follow, new varieties of all shapes and sizes began to appear throughout the Imperial Russian Empire. <br>Today there are at least fifty varieties of black tomato found in the territories of the former Soviet Union, as well as nearly a dozen other types of new black tomatoes which have cropped up elsewhere, most notably in Germany, the former Yugoslavia and the United States.<br>Besides their extremely dark colours, black tomatoes are especially noted for their exceptionally rich, earthy tastes. Among all colours, black tomatoes are blessed with the strongest taste and are typically the most admired among true tomato aficionados</p>

</div>

<script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

VT 49 (10 S)

Giant plant (with giant fruits)

Giant Rhubarb Seeds...

Price

€1.95

(SKU: UT 2)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<div id="idTab1" class="rte">

<h2><span style="font-size: 14pt;" class=""><strong>Giant Rhubarb - Seeds (Gunnera manicata)<br></strong></span></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong><span style="font-size: 14pt;">Price for Package of 10 seeds.</span></strong></span></h2>

<div>Gunnera manicata syn. Gunnera brasiliensis is also known as giant rhubarb. It is a perennial herbaceous plant which is native to the mountains of Brasil and Colombia. Giant gunneras are huge ornamental plants that need a lot of space, which are fitted for big gardens with damps areas or ponds. The leaves usually die back in winter, but the plant itself with survive lower temperatures, down to about 14°F (-10°C) and even lower with some protection. This plant can thus be grown in USDA zones 8a and warmer, and could be tried in sheltered places in zones 7.</div>

<div>This plant has huge decidious leaves, that can be up to 8 ft (2,40 m) wide in its native area. Leaf stems are thorny, and can be up to 4 or 5 ft. (Up to 1,50 m) Gunnera manicata has tiny green-red flowers, which are grouped in erected inflorescences. These inflorescences bear both male and female flowers.</div>

<div>

<p>This plant bear tiny red-green fruits, which are about .1 in (2.5 mm) long.</p>

</div>

<div>Gunnera manicata requiert les expositions suivantes : ombre,mi-ombre,lumière</div>

<div>These plants thrive in damp bog conditions, in a moist and fertile soil.</div>

</div><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

UT 2

Giant plant (with giant fruits)

The Kelsae Giant Onion Seeds

Price

€3.00

(SKU: MHS 147)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8" />

</head>

<body>

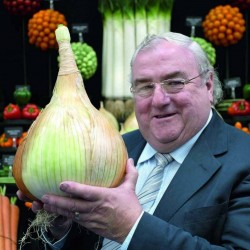

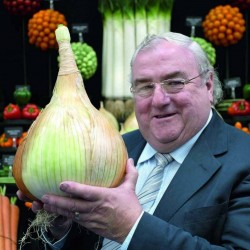

<h2><strong>The Kelsae Giant Onion Seeds</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong><span style="color: #ff0000;">Price for Package of 8 or 15 seeds.</span><br /></strong></span></h2>

<div>110 days. Allium cepa. Plant produces giant 4kg sweet white onion. The Kelsae Sweet Giant Onion holds the Guinness World Record for the Largest Onion in the World at at nearly 15 lb 5.5 oz and 33 inches diameter! It has a unique mild sweet flavor. Impress your neighbors and try growing a World Record size onion. Long day variety suitable for Northern regions.</div>

</body>

</html>

MHS 147 (15 S)

Variety from United States of America

Blue Tomato Seeds "Bosque...

Price

€2.50

(SKU: VT 11)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>Amazing Bosque Blue Tomato Seeds Organically Grown</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 10 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p>Parent plants were grown organically. The Bosque Blue tomato is a select strain bred here from the Oregon State Universit y P20 Blue tomato. The dark blue is t he result of antioxidant compounds (Ant hroc ynan) in the tomatoes skin, (like a blueberry), so not onl its beautiful, it is good for you! The more sun the fruit gets, the more blue color becomes. The fruit is perfect for salads, about 2" in diameter.</p>

<p>Ripe fruit in about 65- 70 days from transplant . Seeds are from open pollinated plants. You can save your seeds year after year to have the true Heirloom Tradition</p><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

VT 11 (10 S)

Coming Soon

Black Amber Cane Sorgham...

Price

€1.55

(SKU: MHS 74)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2><strong>Black Amber Cane Sorghum Seeds (Sorghum Bicolor)</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 10 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p><i><b>Sorghum bicolor</b></i>, commonly called<span> </span><b>sorghum</b><span> </span>(<span class="nowrap"><span class="IPA nopopups noexcerpt">/<span><span title="/ˈ/: primary stress follows">ˈ</span><span title="'s' in 'sigh'">s</span><span title="/ɔːr/: 'ar' in 'war'">ɔːr</span><span title="/ɡ/: 'g' in 'guy'">ɡ</span><span title="/ə/: 'a' in 'about'">ə</span><span title="'m' in 'my'">m</span></span>/</span></span>) and also known as<span> </span><b>great millet</b>,<span> </span><i><b>durra</b></i>,<span> </span><i><b>jowari</b></i>, or<span> </span><b>milo</b>, is a<span> </span>grass<span> </span>species cultivated for its<span> </span>grain, which is used for food for humans, animal feed, and ethanol production. Sorghum originated in Africa, and is now cultivated widely in tropical and subtropical regions.<sup id="cite_ref-4" class="reference">[4]</sup><span> </span>Sorghum<span> </span>is the world's fifth-most important<span> </span>cereal<span> </span>crop after<span> </span>rice,<span> </span>wheat,<span> </span>maize, and<span> </span>barley.<span> </span><i>S. bicolor</i><span> </span>is typically an annual, but some cultivars are perennial. It grows in clumps that may reach over 4 m high. The grain is small, ranging from 2 to 4 mm in diameter.<span> </span>Sweet sorghums<span> </span>are sorghum cultivars that are primarily grown for forage, syrup production, and ethanol; they are taller than those grown for grain.<sup id="cite_ref-FAO_5-0" class="reference"></sup><sup id="cite_ref-6" class="reference"></sup></p>

<p><i>S. bicolor</i><span> </span>is the cultivated species of sorghum; its wild relatives make up the botanical genus<span> </span><i>Sorghum</i>.</p>

<h2><span class="mw-headline" id="Cultivation">Cultivation</span></h2>

<div class="thumb tright">

<div class="thumbinner"><img alt="" src="https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/Sorghum_head_in_India.jpg/220px-Sorghum_head_in_India.jpg" width="220" height="179" class="thumbimage">

<div class="thumbcaption">

<div class="magnify"></div>

Seed head of sorghum in India</div>

</div>

</div>

<div class="thumb tright">

<div class="thumbinner"><img alt="" src="https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/Turpan_Millet.jpg/170px-Turpan_Millet.jpg" width="170" height="255" class="thumbimage">

<div class="thumbcaption">

<div class="magnify"></div>

Sorghum with a recurved peduncle trait, Turpan basin, Xinjiang, China In some varieties and in certain conditions, the heavy panicle will make the young soft peduncle bend, which then will lignify in this position. Combined with awned inflorescence, this forms a two-fold defence against birds.</div>

</div>

</div>

<p>The leading producers of<span> </span><i>S. bicolor</i><span> </span>in 2011 were Nigeria (12.6%), India (11.2%), Mexico (11.2%), and the United States (10.0%).<sup id="cite_ref-AGMRC_7-0" class="reference">[7]</sup><span> </span>Sorghum grows in a wide range of temperatures, high altitudes, and toxic soils, and can recover growth after some drought.<sup id="cite_ref-FAO_5-1" class="reference">[5]</sup><span> </span>It has five features that make it one of the most drought-resistant crops:</p>

<ul>

<li>It has a very large root-to-leaf surface area ratio.</li>

<li>In times of drought, it rolls its leaves to lessen water loss by transpiration.</li>

<li>If drought continues, it goes into dormancy rather than dying.</li>

<li>Its leaves are protected by a waxy cuticle.</li>

<li>It uses<span> </span>C4 carbon fixation<span> </span>thus using only a third the amount of water that C3 plants require.</li>

</ul>

<p>Richard Pankhurst<span> </span>reports (citing Augustus B. Wylde) that in 19th-century<span> </span>Ethiopia,<span> </span><i>durra</i><span> </span>was "often the first crop sown on newly cultivated land", explaining that this cereal did not require the thorough ploughing other crops did, and its roots not only decomposed into a good fertilizer, but they also helped to break up the soil while not exhausting the<span> </span>subsoil.<sup id="cite_ref-8" class="reference"></sup></p>

<h2><span class="mw-headline" id="Uses">Uses</span></h2>

<div class="thumb tright">

<div class="thumbinner"><img alt="" src="https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Sorgho_rouge_blanc.jpg/220px-Sorgho_rouge_blanc.jpg" width="220" height="165" class="thumbimage">

<div class="thumbcaption">

<div class="magnify"></div>

Red on white sorghum grains</div>

</div>

</div>

<p>Sorghum is cultivated in many parts of the world today. In the past 50 years, the area planted with sorghum worldwide had increased by 66%.<sup id="cite_ref-AGMRC_7-1" class="reference"></sup>. The grain finds use as food, for making liquor, animal feed, or making bio based ethanol.</p>

<h3><span class="mw-headline" id="Culinary_use">Culinary use</span></h3>

<p>In many parts of Asia and Africa, its grain is used to make flatbreads that form the staple food of many cultures.<sup id="cite_ref-9" class="reference"></sup><sup id="cite_ref-10" class="reference"></sup><span> </span>The grains can also be popped in a similar fashion to popcorn.</p>

<table class="infobox nowrap"><caption>Sorghum</caption>

<tbody>

<tr>

<th colspan="2">Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz)</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<th scope="row">Energy</th>

<td>1,418 kJ (339 kcal)</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td colspan="2"></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th scope="row">

<div><b>Carbohydrates</b></div>

</th>

<td>

<div>74.63 g</div>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th scope="row">Dietary fiber</th>

<td>6.3 g</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td colspan="2"></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th scope="row">

<div><b>Fat</b></div>

</th>

<td>

<div>3.30 g</div>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td colspan="2"></td>

</tr>

<tr>

<th scope="row">

<div><b>Protein</b></div>

</th>

<td>

<div>11.30 g</div>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td colspan="2">

<div class="plainlist">

<ul>

<li>Units</li>

<li>μg =<span> </span>micrograms • mg =<span> </span>milligrams</li>

<li>IU =<span> </span>International units</li>

</ul>

</div>

</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td colspan="2" class="wrap"><sup>†</sup>Percentages are roughly approximated using<span> </span>US recommendations<span> </span>for adults.</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>

<p>Sorghum is one of a number of grains used as wheat substitutes in<span> </span>gluten-free<span> </span>recipes and products.</p>

<p>In<span> </span>India, where it is commonly called<span> </span><i>jwaarie, jowar, jola</i>, or<span> </span><i>jondhalaa</i>, sorghum is one of the staple sources of nutrition. An Indian bread called<span> </span><i>bhakri, jowar roti</i>, or<span> </span><i>jolada rotti</i><span> </span>is prepared from this grain.</p>

<p>In<span> </span>Korea, it is cooked with rice, or its flour is used to make cake called<span> </span><i>susu bukkumi</i>.</p>

<p>Sorghum was ground and the flour was the main alternative to wheat in northern China for a long time.</p>

<p>In<span> </span>Central America, tortillas are sometimes made using sorghum. Although corn is the preferred grain for making tortillas, sorghum is widely used and is well accepted in<span> </span>Honduras. White sorghum is preferred for making tortillas.<sup id="cite_ref-:1_11-0" class="reference">[11]</sup><span> </span>Sweet sorghum<span> </span>syrup is known as molasses in some parts of the U.S., although it is not true<span> </span>molasses.</p>

<h3><span class="mw-headline" id="Alcoholic_Beverage">Alcoholic Beverage</span></h3>

<p>In<span> </span>China, sorghum is known as<span> </span><i>gaoliang</i><span> </span>(高粱), and is<span> </span>fermented<span> </span>and<span> </span>distilled<span> </span>to produce one form of clear spirits known as<span> </span><i>baijiu</i><span> </span>(白酒) of which the most famous is<span> </span>Maotai<span> </span>(or Moutai). In<span> </span>Taiwan, on the island called<span> </span>Kinmen, plain sorghum is made into sorghum liquor.In several countries in Africa, including<span> </span>Zimbabwe,<span> </span>Burundi,<span> </span>Mali,<span> </span>Burkina Faso,<span> </span>Ghana, and<span> </span>Nigeria, sorghum of both the red and white varieties is used to make traditional opaque<span> </span>beer. Red sorghum imparts a pinkish-brown colour to the beer.<sup id="cite_ref-12" class="reference">[12]</sup></p>

<h3><span class="mw-headline" id="Bio-based_ethanol">Bio-based ethanol</span></h3>

<p>In<span> </span>Australia,<span> </span>South America, and the<span> </span>United States, sorghum grain is used primarily for livestock feed and in a growing number of ethanol plants.<sup id="cite_ref-13" class="reference">[13]</sup><span> </span>In some countries, sweet sorghum stalks are used for producing biofuel by squeezing the juice and then fermenting it into<span> </span>ethanol.<sup id="cite_ref-14" class="reference">[14]</sup><span> </span>Texas A&M University<span> </span>in the United States is currently running trials to find the best varieties for ethanol production from sorghum leaves and stalks in the USA.<sup id="cite_ref-15" class="reference">[15]</sup></p>

<h3><span class="mw-headline" id="Other_uses">Other uses</span></h3>

<p>It is also used for making a traditional corn<span> </span>broom.<sup id="cite_ref-16" class="reference">[16]</sup>The reclaimed stalks of the sorghum plant are used to make a decorative<span> </span>millwork<span> </span>material marketed as<span> </span>Kirei board.</p>

<h2><span class="mw-headline" id="Agricultural_uses">Agricultural uses</span></h2>

<p>It is used in feed and pasturage for livestock. Its use is limited, however, because the starch and protein in sorghum is more difficult for animals to digest than the starches and protein in corn.<sup class="noprint Inline-Template Template-Fact">[<i><span title="This claim needs references to reliable sources. (December 2012)">citation needed</span></i>]</sup><span> </span>Research is being done to find a process that will predigest the grain. One study on cattle showed that steam-flaked sorghum was preferable to dry-rolled sorghum because it improved daily weight gain.<sup id="cite_ref-AGMRC_7-2" class="reference">[7]</sup><span> </span>In hogs, sorghum has been shown to be a more efficient feed choice than corn when both grains were processed in the same way.<sup id="cite_ref-AGMRC_7-3" class="reference">[7]</sup></p>

<p>The introduction of improved varieties, along with improved management practices, has helped to increase sorghum productivity. In India, productivity increases are thought to have freed up six million hectares of land. The<span> </span>International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics<span> </span>in collaboration with partners produces improved varieties of crops including sorghum. Some 194 improved cultivars of sorghum from the institute have been released.<sup id="cite_ref-17" class="reference">[17]</sup></p>

<h2><span class="mw-headline" id="Research">Research</span></h2>

<p>Research is being conducted to develop a genetic cross that will make the plant more tolerant to colder temperatures and to unravel the drought tolerance mechanisms, since it is native to tropical climates.<sup id="cite_ref-18" class="reference">[18]</sup><sup id="cite_ref-19" class="reference">[19]</sup><span> </span>In the United States, this is important because the cost of corn was steadily increasing due to its use in ethanol production for addition to gasoline. Sorghum silage can be used as a replacement of corn silage in the diet for<span> </span>dairy cattle.<sup id="cite_ref-Brouk_20-0" class="reference">[20]</sup><span> </span>More research has found that sorghum has higher nutritional value compared to corn when feeding dairy cattle, and the type of processing is also essential in harvesting the grain's maximum nutrition. Feeding steam-flaked sorghum showed an increase in milk production when compared to dry-rolling.<sup id="cite_ref-Brouk_20-1" class="reference">[20]</sup></p>

<p>Additional research is being done on sorghum as a potential food source to meet the increasing global food demand. Sorghum is resistant to drought- and heat-related stress. The genetic diversity between subspecies of sorghum makes it more resistant to pests and pathogens than other less diverse food sources. In addition, it is highly efficient in converting solar energy to chemical energy, and also in use of water.<sup id="cite_ref-:0_21-0" class="reference">[21]</sup><span> </span>All of these characteristics make it a promising candidate to help meet the increasing global food demand. As such, many groups around the world are pursuing research initiatives around sorghum (specifically<span> </span><i>Sorghum bicolor</i>):<span> </span>Purdue University,<sup id="cite_ref-22" class="reference">[22]</sup>HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology,<sup id="cite_ref-:0_21-1" class="reference">[21]</sup><span> </span>Danforth Plant Science Center,<sup id="cite_ref-:0_21-2" class="reference">[21]</sup><span> </span>the<span> </span>University of Nebraska,<sup id="cite_ref-23" class="reference">[23]</sup><span> </span>and the<span> </span>University of Queensland<span> </span><sup id="cite_ref-24" class="reference">[24]</sup><span> </span>among others. The University of Queensland is involved with pre-breeding activities, which are extremely successful and still are in progress using<span> </span>crop wild relatives<span> </span>as donors along with popular varieties as recipients to make sorghum more resistant to biotic stresses.</p>

<p>Another research application of sorghum is as a biofuel. Sweet sorghum has a high sugar content in its stalk, which can be turned into ethanol. The biomass can be burned and turned into charcoal, syn-gas, and bio-oil.</p><script src="//cdn.public.n1ed.com/G3OMDFLT/widgets.js"></script>

MHS 74 (10 S)

Giant plant (with giant fruits)

Variety from Peru

Peruvian Giant Red Sacsa...

Price

€2.25

(SKU: P 280)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8" />

<h2><strong>Peruvian Giant Red Sacsa Kuski Corn Seeds</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 5 or 10 seeds.</strong></span></h2>

<p><span style="color: #000000; font-family: georgia, palatino, serif; font-size: 14pt;">Large-kernel variety of field corn from the Andes, kernel is white-red color. Excellent for cooking and baking, very sweet and large grain so it is best used for cooking.</span></p>

<p><span style="color: #000000; font-family: georgia, palatino, serif; font-size: 14pt;">One of the most widely-consumed foodstuffs in Peruvian cuisine. This corn has been planted in Peru since at least 1200 BC. The ancient Peruvian farmers achieved a degree of sophistication in the selection and creation of new varieties which adapted to varying terrains and climates.</span></p>

<p><span style="color: #000000; font-family: georgia, palatino, serif; font-size: 14pt;">Sixteenth-century Spanish chronicler Bernabé Cobo wrote how in ancient Peru one could find corn (known locally as choclo) in every color under the sun: white, yellow, purple, black, red and mixed. Today, farmers along the Peruvian coast, highlands and jungle grow more than 55 varieties of corn, more than anywhere else on Earth.</span></p>

<p><span style="color: #000000; font-family: georgia, palatino, serif; font-size: 14pt;">Native historian Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, in his Royal Commentaries of the Incas, wrote in detail on eating habits in colonial times. In those days, corn was a key part of nutritional needs, and the locals called it Sara, eating it roasted or boiled in water. On major occasions, they milled the kernels to bake a type of bread called tanta or huminta. For solemn events such as the Festival of the Sun (Inti Raymi), they would bake breadrolls called zancu. The Peruvian corn was also roasted and called the same today as it was then: cancha (the predecessor of popcorn).</span></p>

<p><span style="color: #000000; font-family: georgia, palatino, serif; font-size: 14pt;">Today, Peru features regional varieties on ways to prepare delicious dishes based on corn. In northern Peru, the locals are particularly fond of pepián, a stew based on grated corn kernels mixed with onion, garlic and the chilli pepper and which takes on a particularly heightened flavor when cooked with turkey. Arequipa inhabitants prepare a dish called soltero (beans, corn, onion and dressing made from fresh cheese). In the jungle, one of the most typical dishes, inchi cache, is made from chicken cooked in a stew made of roasted corn and peanuts. Desserts include the sanguito (made from yellow cornflour, cooking fat, raisins and a sugarcane molasses called chancaca).</span></p>

<p><span style="color: #000000; font-family: georgia, palatino, serif; font-size: 14pt;">Peruvian Corn is also used to make cornmash pastries called tamales and humitas, which can come in a wide range of colors and flavors (green, brown and yellow; sweet and savory); peruvian corn is also the main ingredient of the chicha morada (drink made from purple corn) or chicha de jora (fermented corn beer) and the sweet purple corn jelly called mazamorra, for special occasions.</span></p>

P 280 5-S NS

Variety from Serbia

Popcorn 50 seeds - Grow...

Price

€1.95

(SKU: VE 104)

Seeds Gallery EU,

5/

5

<h2 class=""><strong>Popcorn seeds - Grow your own</strong></h2>

<h2><span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>Price for Package of 50 (10g) seeds. </strong></span></h2>

<p>100% NATURAL POPCORN</p>

<p>NON-GMO, NOT GENETICALLY MODIFIED. SIMPLY PURE AND NATURAL!</p>

<p><b>Popcorn</b><span> </span>(<b>popped corn</b>,<span> </span><b>popcorns</b><span> </span>or<span> </span><b>pop-corn</b>) is a variety of<span> </span>corn<span> </span>kernel, which expands and puffs up when heated.</p>

<p>A popcorn kernel's strong hull contains the seed's hard, starchy<span> </span>endosperm<span> </span>with 14–20% moisture, which turns to steam as the kernel is heated.<span> </span>Pressure<span> </span>from the steam continues to build until the hull ruptures, allowing the kernel to forcefully expand from 20 to 50 times its original size—and finally, cool.<sup id="cite_ref-ref5_1-0" class="reference">[1]</sup></p>

<p>Some<span> </span>strains<span> </span>of corn (taxonomized as<span> </span><i>Zea mays</i>) are cultivated specifically as popping corns. The<span> </span><i>Zea mays</i><span> </span>variety<span> </span><i>everta,</i><span> </span>a special kind of<span> </span>flint corn, is the most common of these.</p>

<p>The six major types of corn are<span> </span>dent corn,<span> </span>flint corn,<span> </span>pod corn, popcorn,<span> </span>flour corn, and<span> </span>sweet corn.<sup id="cite_ref-2" class="reference"></sup></p>

<h2><span class="mw-headline" id="History">History</span></h2>

<p>Corn was first domesticated about 10,000 years ago in what is now<span> </span>Mexico.<sup id="cite_ref-3" class="reference">[3]</sup><span> </span>Archaeologists discovered that people have known about popcorn for thousands of years. In Mexico, for example, remnants of popcorn have been found that date to around 3600 BC.<sup id="cite_ref-4" class="reference">[4]</sup></p>